‘Fando and Lis’ and ‘The Prayer’

‘Fando and Lis’ and ‘The Prayer’

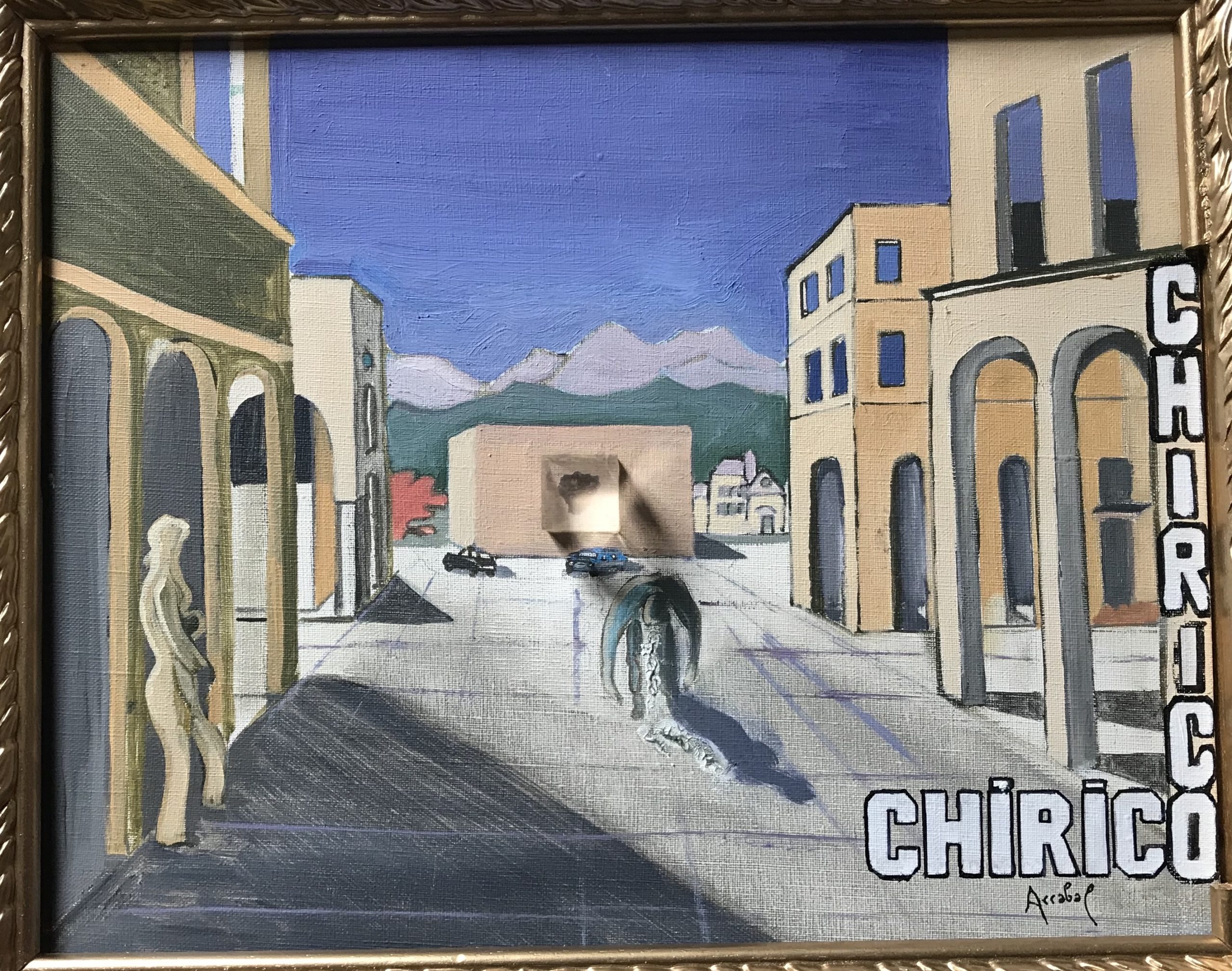

by Fernando Arrabal

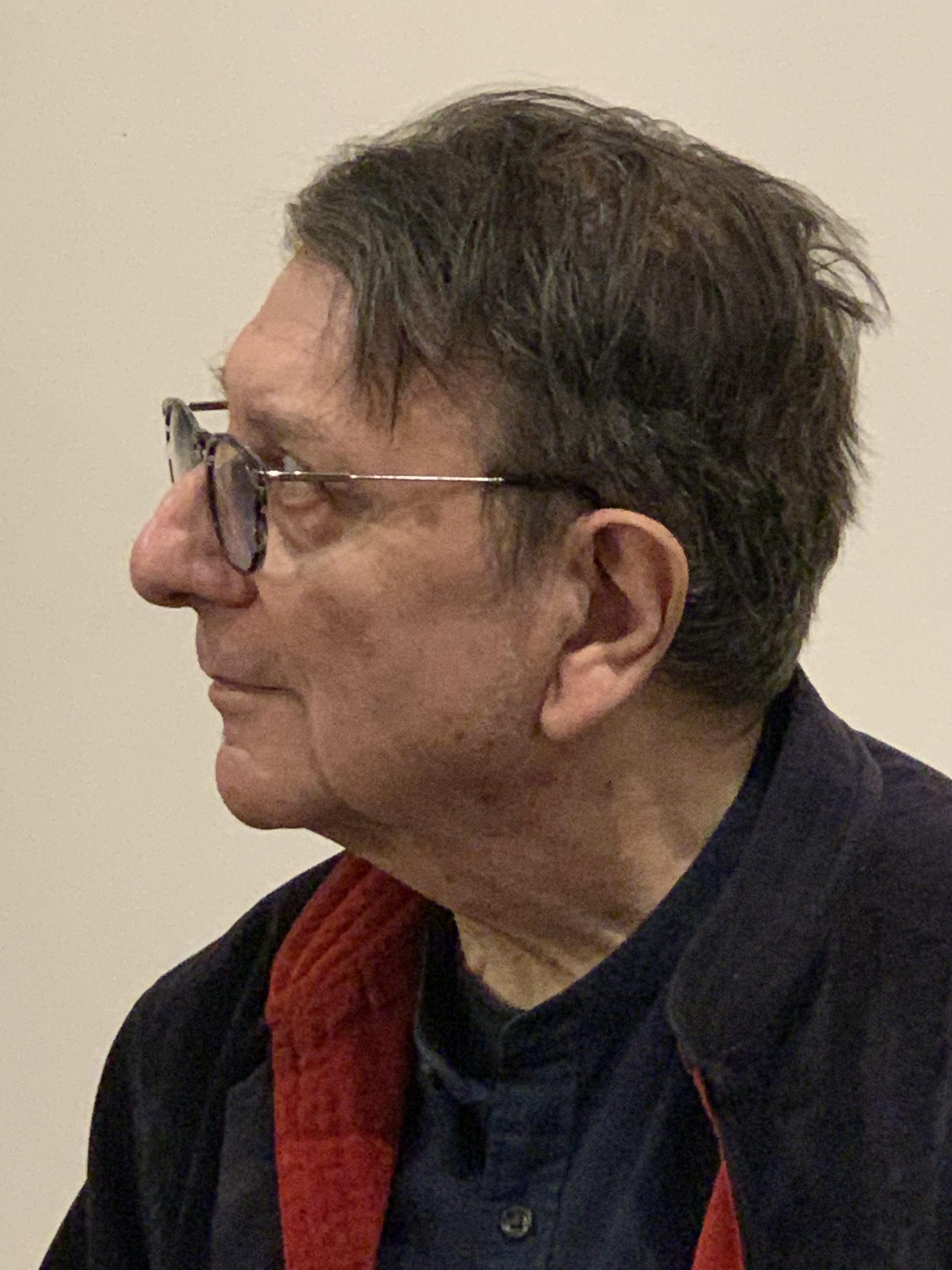

Peris Michailidis, director . Born in Alexandria, Egypt. He enrolled at the Drama School of National Theatre of Northern Greece in 1974 and he participated in seminars intructed by Grotowski and his partners at the University of Rome. He worked as an actor at the National Theatre of Northern Greece from 1986 until 1992 and as a director for three years, 2005-’08. He created the “Machine” Theatre Company presenting pioneering performances on the works of Beckett, Seneca, Dostoevsky, Bernhard etc. In recent years I’ve acted in Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment”.

Actors:

Dimitris Kapamas,

Arriti Kechagia,

Yiannis Petridis,

Baptised to the plays of Arrabal by our teacher, Peris Michailidis, we found there what we want to say with our performance. The abyss of the human soul, the cruelty of human relationships, how love and violence are interconnected and all of this in the manner of Fando and Lis.

[Fando moves towards Lis. He looks at her with respect, very sadly approaches her. He holds her, sits her up. Her head keeps falling, inert. Fando doesn’t say anything. (The three men under the umbrella, standing up and solemn, have taken their hats off.) Fando rests her on the ground with great care, then arranges his mantle. Fando is close to tears. Suddenly he rests his forehead on her belly. Although we don’t hear him, he is probably crying.]

***

Fando and Lis

by Fernando Arrabal

Characters:

Lis: A woman in a pram.

Fando: The man who takes her to Tar,

and the three men under the umbrella:

Namur

Mitaro

Toso

A play in five scenes.

First Scene

[Fando and Lis sit on the ground. Next to them is a very large pram, black, old and tattered, with thick rubber wheels and rusty spokes. On the sides, attached with strings, we can see a certain number of objects, amongst which there are a drum, a rolled up blanket, a fishing rod, a leather bag, and a pan. Lis has her two legs paralysed.]

Lis: But I will die and nobody will remember me.

Fando: [Very tender.] No, Lis, I will remember you and I will come and see you in the cemetery with a flower and a dog.

[Long pause. Fando looks at Lis.]

Fando: [Moved.] And at your funeral I will softly sing the song: “What a beautiful funeral. What a beautiful funeral.” That tune is so easy to hold. [He looks at her quietly and adds satisfied:] I will do that for you.

Lis: You love me so much.

Fando: But I’d rather you don’t die. [Pause.] I will be so sad, the day you die.

Lis: You will be sad? Why?

Fando: [Apologising.] I don’t know.

Lis: You only say that because you’ve heard someone else saying it. And that means you won’t be sad. You’re always deceiving me.

Fando: No Lis, I’m honest. I will be very sad.

Lis: Will you cry?

Fando: I’ll do my best, but I don’t know if I will be able to.

Lis: Don’t know if I will be able to. Don’t know if I will be able to. Do you think that’s an answer?

Fando: Believe me, Lis.

Lis: But, believe what?

Fando: [Thinking.] I don’t know exactly. Just tell me you believe me.

Lis: [As an automaton.] I believe you.

Fando: That’s not in the right tone.

Lis: [Cheerfully.] I believe you.

Fando: That’s not right either, Lis. [Humble.] Lis, when you want to, you know very well how to say things.

Lis: [In a different tone, still not sincere.] I believe you.

Fando: [Discouraged.] No, Lis, no. Not like that. Try it again.

Lis: [Puts in an effort, but her words do not sound more sincere than before.] I believe you.

Fando: [Very sad.] No, no Lis. What are you doing? How nasty you are to me! Try a bit harder.

Lis: [Not reaching her goal.] I believe you.

Fando: [Violently.] No, no that’s not it.

Lis: [In a desperate effort.] I believe you.

Fando: [Even more violent.] And neither like that.

Lis: [Sincere.] I believe you.

Fando: [Emotional, touched.] Lis! You believe me?

Lis: [Touched herself.] Yes, I believe you.

Fando: Oh, I’m so happy, Lis!

Lis: I believe you because when you talk, you resemble a rabbit and when you sleep with me you let me take the whole blanket and you catch cold.

Fando: That’s nothing.

Lis: And especially because in the morning you wash me by the fountain and because, like that, I don’t have to do it. You know, I don’t like doing it.

Fando: [After a pause, with a resolute air.] Lis, I want to do lots of things for you.

Lis: How many?

Fando: [He thinks.] As many as possible.

Lis: OK, then what you have to do is, to fight for your life.

Fando: That’s very difficult.

Lis: That’s the only thing you could do for me.

Fando: Fight for my life? What are you talking about? [A moment.] You are not joking are you? [Very serious.] But, Lis, I don’t understand why I should fight and maybe then if I did know, I might not have the necessary strength, and if I’d have the strength, I don’t know if it would help me to succeed.

Lis: Fando, make an effort.

Fando: Make an effort? [Pause.] Maybe that will be easier.

Lis: We have to agree.

Fando: And you are sure that will help us?

Lis: Almost sure.

Fando: [Thinks.] But help us how?

Lis: It doesn’t matter, what counts is, that it helps.

Fando: Everything is so simple for you.

Lis: No, for me too, everything is very difficult.

Fando: But you find a solution for everything.

Lis: No, I never find solutions, what happens is, that I lie when I say that I found one.

Fando: But, that’s not fair.

Lis: I know it’s not fair. But, since I’m never asked anything, it doesn’t make any difference. And anyway, it makes me look good.

***_____________________________

Fifth Scene

[On stage, the three men under the umbrella.]

Mitaro: He promised her, when she died, he would go and visit her in the cemetery with a flower and a dog.

Namur: No, that’s not it. What happened was that she told him that she wanted to take her own life and he replied to her that that would be the best thing she could do. So she and her two companions killed the man with the tickets to be able to pay in time for the hire of the box-tricycle. And so they went to buy anchovy sandwiches and paid for hiring it, but the police came to find them and although they didn’t see anything wrong in it, they were arrested.

Mitaro: Yes, I remember that one of them spend his time sleeping and that he didn’t want to think because it was annoying and so his friend told him that it would be better to think of silly stories and he replied he didn’t know … [He thinks.]. But that is a completely different story. The one I am talking about is the story of the man that drove around a paralysed woman in a pram trying to get to Tar. [94] I remember that he was told that it was very difficult to get to Tar but that they should try anyway, but later on he told her that when they would arrive, he would compose for her a lot of beautiful songs like the one about the feather and that he would accompany them with the drum and then they kissed.

Namur: No, because then she discovered he was carrying handcuffs around and was going to put them on her. He said it was nothing, but he held on to them. So she got angry with him and told him that …

Mitaro: No, no, you change everything, you forget everything and you mix everything up. What happened was that after that a police officer arrived, who we didn’t understand all too well and the old flute player told him that he didn’t understand him because he was as bad as his feet and then the other one got really angry. [Pause.] And it was at that moment that those two men arrived, one of which played the harmonium and the other a type writer.

Namur: Ah, yes, I remember well, they were in a car cemetery. And their lives were really sad because they couldn’t switch their instruments.

Mitaro: No, no, they could.

Namur: But that was after. And then straight away the clever man arrived and made them see all that he knew and they just continued to be morons.

Mitaro: No, no, then, what happened was that she and he started playing at thinking. But since he didn’t know how to take on a good position, he thought really badly and when she showed him what position he should put himself in, he could only think about death.

Toso: What happened is that we got ourselves under an umbrella and we tried to go to Tar. But you took so long discussing the precautions to take that, after we finally left, we were delayed considerably, as usual.

[Namur and Mitaro followed Toso’s words with a clear annoyance.]

Namur: [Interrupting him.] And all that to what purpose?

Mitaro: You see how you always get in our way.

[Toso kees quiet.]

_______________________________________________________________________

Arrabal, Fernando

Arrabal, Fernando 1932-

Arrabal attacks in his plays political, theological, linguistic, and psychological restrictions on freedom. A recipient of the Grand Prix du Théâtre, Arrabal is best known for L’Architecte et l’Empereur d’Assyrie. (See also CLC, Vol. 2, and Contemporary Authors, Vols. 9-12, rev. ed.)

[Arrabal’s first novel, Baal Babylone,] serves as a good introduction to [his] later work, for it is a semi-autobiographical narrative that gives many insights into the dramatist’s not too secret traumas. Writing in a deceptively simple, childlike language, Arrabal sets forth the portrait of a Spanish child at a period perhaps immediately after the Civil War. The child’s father is gone, but his presence remains vivid for the boy. The child must cling to his father’s memory as a means to escape from his odious, oppressive surroundings. It seems that the boy’s mother, a domineering woman possessed with her own martyrdom, has denounced the father to the police « for his own good. » The mother is thus the prototype for the gallery of sadistic figures who, in Arrabal’s theater, cruelly but joyously destroy what they profess to love. In Baal Babylone the child refuses to surrender to his mother and her voracious demands. The father’s memory thus becomes a symbol of deliverance in the smothering atmosphere where a devouring maternal love is sanctified by the duties the state church would impose upon the child. The boy’s silent revolt is made manifest when he exposes himself and urinates before a convent grill. Arrabal’s theater, in which exhibitionism, chamber pots, and urinations are frequent images, continues this scatological form of revolt, though in a less symbolic manner. For in his theater, Arrabal’s revolt becomes a ritual of assault that attacks with unmediated directness.

Guilt, oppression, sadism, childish revolt, erotic fantasies, matricide, all of these fit together to form a surprisingly coherent dramatic world, whatever may be the excesses that Arrabal gives into at times. And since Arrabal published his first play some ten years ago, his work has undergone an evolution that points to a greater understanding of the theater. He began with short plays, such as Orison, Fando et Lis, and Guernica, in which the influences of such writers as Ionesco and Adamov is quite evident. His work has evolved toward more complex spectacles in which ritual and ceremony are used to give more stylized expression to his obsessions. Plays such as Le Grand Cérémonial and Concert dans un oeuf should be viewed as erotic ballets or celebrations into which the spectator should enter for purposes of communion and exorcism. Arrabal has also experimented with « pure » spectacles where a kinetic mise en scène, using motifs from Klee, Mondrian, and Delaunay, becomes an abstract drama. In both his ritual and his abstract works, Arrabal again calls to mind Artaud and his call for a total spectacle…. In 1967, this search for a freer theater culminated in L’Architecte et l’Empereur d’Assyrie. In this play Arrabal attained a synthesis between abstract mime and poetical fantasy, a synthesis which marks his mastery of the stage and perhaps of his personal anxieties. (pp. 174-76)

Baal Babylone‘s mother-child relation, which might be likened to an inverted Oedipal relationship, is savagely exploited in one of Arrabal’s earliest plays, Les Deux Bourreaux (translated as The Executioners). In this work of patent sadism, the mother-martyr not only turns the father over to the police, but she happily watches as he is tortured by two anonymous executioners. To demonstrate her beneficent affection for him, she rubs salt and vinegar into his wounds, which completes this intentional murder of Laius. In Les Deux Bourreaux the mother has two sons, one of whom is a model of filial loyalty toward her. His example points up the rebellion of the ungrateful son who resists his mother’s carnivorous affection. Yet the mother is too powerful and convinces the rebel to beg her forgiveness for the unnatural act of turning against maternal love. The father thus disposed of, the mother can retire to enjoy her son’s exclusive love.

It would thus appear that an ambivalent Oedipal relationship, although directly portrayed in a relatively limited number of plays, is central to an understanding of Arrabal’s fantasies. Two of his later, more developed plays cast more light on the mother-son relation and are worth examining in this respect. The first play, Le Grand Cérémonial, is a bizarre « ceremonial » in which a hunchbacked lover, appropriately named Cavanosa, plays the rôle of the doting yet rebellious son. Cavanosa, a seemingly emasculated lover, first claims to have murdered his mother and then claims to have murdered each night a girl whom he has loved. In fact, it seems that he has been reduced to making love to a collection of life-sized dolls that he beats and fondles with equal relish. Yet if Cavanosa is capable of transferring the erotic relationship he has with his mother, his only gesture of love can be to kill the woman he has taken to bed—the bed being the altar on which he sacrifices to the demands of maternal love. The suggested pattern of homicidal coitus is broken by Sil, a lover who, against her will, escapes death. She is offered to the mother as a slave to be tortured at the mother’s pleasure. Such is the price of love in Arrabal’s theater, where no amorous affair can be complete without whips and chains, or at least the confining prison of a baby carriage. And a more striking portrayal of a repressed Oedipal development, displaced as it may be, can hardly be imagined. (p. 176)

For Arrabal, then, love, as derived from the mother-son symbiosis, is either a form of bondage of a homicidal activity. Slavery and murder form the two poles of love’s dialectic. So it is hardly surprising that sadism, a mediator that reconciles both bondage and destruction, is love’s principal manifestation in this theater of violent fantasy…. Arrabal’s theater of sadism seems to be a direct reply to Artaud’s cry for « a new idea of eroticism and cruelty » in the theater…. The metaphysics of cruelty is at the heart of Arrabal’s theater. Metaphysics, as Artaud used the term in its original sense, means a world beyond the world that naturalistic and even lyrical theater had tried to incorporate as stage reality. Theatrical metaphysics is, to recall the language of Arrabal’s manifesto, the sublimation of the theater, the « raising up » and the creation of new fantasies that can be celebrated only on the autonomous stage. Thus the theater, seen in this light, seems to be the most natural outlet for Arrabal’s obsessions with eroticism and cruelty, obsessions that have led him to the creation of ritual forms that present, in Artuad’s sense, a metaphysics of sadism. (pp. 177-78)

A more traditional portrayal of sadism is to be found in Fando et Lis. These two infantile lovers are hopelessly traveling to Tar, an enigmatic land possessing the same degree of reality as Kafka’s castle. Lis, a paralytic, rides in a baby carriage pushed by Fando. Fando feels a continual compulsion to put chains on his captive inamorata, and when she complains, he finally beats her to death in a fit of childish rage. He is immediately and uncomprehendingly repentant for his act, but his repentance is quite as meaningless as the murder itself. The dramatic force of Fando et Lis is not in its neo-Kafka statement of absurdity nor in its assault upon the banalities of language and pseudo-logic. Beckett and Ionesco are certainly more convincing than Arrabal in conveying a drama of existential anguish or in conjuring the destructive powers of words. Rather it is in the creation of a closed world of childish sadism and erotic bondage that Arrabal is an original and forceful playwright. The infantile mentality of most of Arrabal’s non-heroes allows him to exploit his themes of sadism and violence with a comic sense that would be denied to a theater of more mature protagonists. His retarded characters play at « forbidden games » which mix horror and tenderness in dreamlike proportions. Yet his characters, ideal partners for the Oedipal relationship in this respect, are endowed with very adult sexual powers and lusts.

In spite of their homicidal fury, most of Arrabal’s protagonists, as children, retain their innocence, or at least the innocence that non compos mentis confers…. Arrabal’s characters often play at being criminals, but, their childish innocence notwithstanding, they are subject to bloody reprisals they cannot hope to grasp.

The obsessive quest for goodness that Arrabal’s infantile heroes undertake serves as a counter-motif to their sadism and lusty criminality. Arrabal’s retarded lovers feel remotely the need to be good, to stop killing or fornicating, although their search for goodness is usually as senseless a whim as their casual murders. (pp. 178-79)

The desire for goodness in Arrabal’s plays is a negative motif that, by its comic futility, points up the blatant cruelty that his characters decidedly prefer. One can also see that the manic quest for goodness in its most puerile form is a part of the obsession with childishness and, hence, a part of the child-parent fantasy that pervades Arrabal’s theater. Goodness as a negation is largely equated with repressing erotic desires, which, in turn, must be viewed in light of the infantile fear of sexuality that runs throughout the plays.

For another aspect of Arrabal’s dialectic of goodness and sadism is his obsessive fear of the sexual act…. [The] mother-son relation carries with it a fear of defilement that counterbalances his sexual fantasies. Defilement must lead to destruction, as in Le Couronnement (The Coronation), where loss of virginity causes death…. Sadism in Arrabal can quickly become a form of anti-eroticism, however enthusiastically his characters may fornicate in chains. This anti-eroticism is undoubtedly infantile, as are his characters’ sadistic antics; it is nonetheless a strong motif as Arrabal’s creation of a dramatic tension founded on lustful bondage and sterile destruction. An anti-eroticism grounded in fear establishes one limit to Arrabal’s fantasy world.

Just as in Baal Babylone the child’s father was an absent presence that weighed upon the child, in Arrabal’s theater it is God the Father whose absence is felt everywhere. In Baal Babylone the father represented a source of deliverance. In the theater an inversion occurs, perhaps illustrating another aspect of the ambivalent mother-son relation and, more especially, showing that God the Father, being identified with the mother, becomes the figure against whom it is necessary to revolt. For in the theater God is a stifling force that must be exorcized by various forms of blasphemy. Arrabal’s blasphemy is peculiarly Catholic and Spanish…. Arrabal’s characters often have a personal hatred of God; yet, their anger with Him is often a result of His refusal to exist. It is difficult to revolt against the absent Father.

While considering the religious motif, special commentary should be given to La Cimetière des voitures. This play has received the most criticism and has been dismissed, on the one hand, for its contrived cleverness and, on the other hand, for the degrading image it presents…. The play does set forth an image of total degradation, but it should also be seen as a mock passion play—one with sociological overtones perhaps. This passion play is another aspect of Arrabal’s rebellious parody of religion, but it also seems to be an attempt to portray a religious vision for our time. La Cimetière des voitures is ambiguous, since it is both blasphemous buffoonery and a celebration honoring the dead Father’s vestigial presence in the presence of his crucified son.

A final important motif in Arrabal’s theater is that of the police state and its arbitrary powers of oppression and torture. Arrabal’s experience during the Spanish Civil War is sufficient to explain his obsession with this nightmarish fantasy. In Les Deux Bourreaux, as shown previously, the mother is associated with the executioners in this theater where pointless cruelty receives the sanction of a nameless, omnipotent state. Indeed, for Arrabal the state is defined through its capacity to inflict torture. La Bicyclette du condamné (The Condemned Prisoner’s Bicycle) gives a variation on this theme when the lascivious lover Tasia allows another nameless pair of executioners to kill her beloved, her final, characteristic act being to nail him in his coffin. Another play, Le Labyrinthe, shows that Kafka’s influence is as much at the heart of Arrabal’s vision of universal guilt and condemnation as is Franco’s Spain. Resembling a dramatized version of The Trial, Le Labyrinthe is set in a forest of blankets from which a traveler, Etienne, cannot escape. The forest’s owner, a father figure possessing absolute power over his domain, chains Etienne to a urinal. In breaking his chains Etienne is brutal to a fellow prisoner who, though nearly paralyzed, hangs himself. Etienne is tried for murder and commits a series of errors that inexorably bring about his condemnation. The play is remarkable for its creation of an atmosphere where innocence, or near innocence, is forced to impeach itself by the relentless logic of arbitrary power. In a comparable fashion, Guernica, a play inspired by Picasso’s painting, also depicts a universe founded upon guilt. A nameless officer’s stare and the sight of his handcuffs are enough to implicate in guilt those who are helplessly caught in the war’s anonymous destruction. Authority, whatever form it may take in Arrabal, is synonymous with gratuitous persecution. The absent father, the possessive mother, and the anonymous state all share this feature.

Arrabal’s obsessive fantasies have given rise to a body of work that is among the most promising of the New Theater. With the modernity of a happening and the courage to face the delirium of our times, it may well come to be among the most significant in this second half of the twentieth century. (pp. 180-83)

Allen Thiher, in Modern Drama (copyright © 1970, University of Toronto, Graduate Centre for Study of Drama; with the permission ofModern Drama), May, 1970.

The latest volume of Arrabal’s theatre [Théâtre 8] contains what the dramatist calls « Deux opéras paniques, » Ars amandi and Dieu tenté par les mathématiques. The juxtaposition of the two appears to be an exercise in antithetical relations.

Ars Amandi belongs to the tradition of haut baroque favored by this most Spanish of self-exiled artists. Since no composer has yet been found for this work, the game of matching a group of musicians, dead and living, to the play proves revealing….

Fridigan, the Parsifal of this mock-ceremony, at once sacred and profane, is embarked on a search for a missing friend, Erasme Marx—the perfect amalgam in name of Renaissance and modern humanism. On his way, the hero encounters the giantess Lys, a Venus in whose garden flower a wide variety of sado-masochistic delights. Two angel-demons, Bana and Ang (could they be body and soul?) attend on this creature who shifts from implacable mistress to victim and martyr. In a gallery of Lys’ medieval castle, life-size mannequins briefly enact the myths they represent: the state of childhood (Le Petit Poucet, Pinocchio), nightmarish fears (Frankenstein, Dracula, King Kong), eternal love (Romeo), jealous passion (Othello), primitive nature (Tarzan), thirst for knowledge (Faust), self-sacrificing agape (Christ, Don Quixote). The pantomime plays within the play are forms of initiation. Only by observing the mannequins’ interpretation of their own lives or of one another’s can Fridigan learn something about the human race, and thus about himself.

When this knight errant first espies Lys she is a gigantic figure covered with swarms of insects (flies? bees?). From the start we feel that Fridigan is torn between fascination and horror at the sight of this Géante turned Charogne. Baudelaire comes to mind, for Fridigan might wish to « Parcourir à loisir ses formes magnifiques, » were he not repulsed by the buzzing of batallions of flies. Yet we must keep in mind that Baudelaire’s Charogne is strangely sensual as she lies « Les jambes en l’air, comme une femme lubrique, » and even alive in the very process of decay.

When Lys is shown next, she is normal-size and engaged in painting a single word from a model. The model says OUI whereas Lys is sketching a large NON on the canvas. Clearly, Fridigan is about to enter an antiworld.

In this universe speech is replaced by singing, but Arrabal makes it eminently clear that this is not a nobler mode of expression. Bana and Ang sing because they stutter when they attempt to speak. Out of politeness, Fridigan imitates them, as Lys does out of charity…. Also, as in Pirandello, appearances are constantly shifting, relations changing. (p. 949)

Could Lys be Spain, or the Spanish people?… If the Spanish motif is emphasized by the projections of Goya’s paintings …, other elements indicate that the nationalist aspect is only a minor theme of this opera. It is in fact a poetic recreation of the history of humanity of which man’s inhumanity to man is an essential part. This is the significance of the tableaux muets played out by the mannequins whose surrealist groupings mockingly reveal the diversity of man’s imaginings. Even in this play within a play the characters do not always play themselves. A Christ-like Fridigan, holding an olive branch, watches this bit of Theatre of the Ridiculous. He is deeply moved, and we are made aware that this moment parallels Parsifal’s first introduction to the Fisher-King’s court. Like Parsifal, Fridigan is still a fool at this time, and his pity is sentimental self-indulgence.

In the course of the play, the hero will have to come to terms with pain and degradation. A Circe-like Lys will bring him down into the mud where they wallow together. She orders Fridigan to prove his love by accepting vilification…. Erotic bliss is followed by images of death. The scene is set for an operation. Fridigan accepts to receive from Lys a mysterious injection. « Je sais que vous voulez me tuer comme vous avez tué mon ami. Mais j’accepte tout. »… Indeed, right after the injection, Fridigan sees his friend Erasme Marx. They are standing against a soft, pink wall. « Where is Lys? » wonders Fridigan, and Erasme answers: « She’s with us. » Lys is once again the giantess of the opening scene, and the two friends are part of her body.

Now we know that Lys was the All, the cosmos. The insects swarming on her form were human beings. Having traveled through the world and the antiworld, Fridigan, the hero, has learned to give up the rational. Only then can he rejoin the dead humanist, Erasme Marx. Arrabal’s Baroque cathedral has turned into a Khmer temple.

Dieu tenté par les mathématiques is an abstract stage-setting written to illustrate the abstract composition of Jean-Yves Bosseur. Bosseur’s « musical battle field » is shared by seventeen musicians who are not told what musical instrument each must play. The score indicates only temporal relations loosely connecting visual and sonorous effects. This is a French equivalent of a John Cage-Merce Cunningham happening.

To match the calculated freedom of Bosseur’s composition, Arrabal has invented a series of planes, surfaces, spinning objects, skipping rubber balls together with live actors as impersonal as—or perhaps more so than—the acting objects. The result is a fascinating « orchestration théâtrale, » as spare as the panic opera is lush. It bears perhaps more novelty for a potential European audience than for Americans who have been exposed to many such manifestations. The same could also be said of the Opera which has little to add to the innovations of the Theatre of the Ridiculous. Arrabal is at his best when his theatricality is less gratuitous, when he deals with a theme which enlists his passions, such as his play about prisoners in one of Franco’s jails … Et ils passèrent des menottes aux fleurs. (p. 950)

Rosette C. Lamont, in French Review, April, 1971.

Fernando Arrabal, in describing his more recent theater as a ceremonie « panique » provides a valuable clue for understanding his earlier works. For this young Spanish playwright, who is better known in France than in his own country, theater is a rigorously ordered ceremony wherein it is indispensable that, beneath an apparent disorder, the presentation be a model of precision, in order that the chaotic confusion of life may be reflected with mathematical clarity. Such concern for precision, though achieving its purest expression in the « Théâtre panique, » is manifestly evident in a 1958 work, not included in the « panique » and largely ignored by critics, La Bicyclette du Condamné. In this one-act piece, the playwright achieves order within chaos by virtue of a circular structure which encompasses even the stage properties and goes far beyond the paradoxical juxtaposition of love-cruelty, goodness-evil, child-man usually mentioned as basic characteristics of Arrabal’s work. (p. 205)

As dramatic structure, the circle is eminently appropriate to contemporary theater, for it aptly parallels modern man’s effort to extricate himself from the chaos left by the dissolution of traditional values—a chaos no less terrifying than that confronted by primitive man. The inevitable result of such circular structure, however, is to leave the spectator in a quandary as to those elements which are missing from the circle itself—beginning, middle, end. Therefore, the staged action seems to be devoid of reason for being, of action itself, and of resolution. Thus, in … La Bicyclette du Condamné, the audience is hard put to know: Who is the condemned man? What is his crime? Who has condemned him? What will be the ultimate result of his punishment? Even were the play’s elements to be reduced to pure interaction, without recourse to dialogue (as is actually the case in many of this writer’s later « panique » works), a distinct circularity would be pervasive, not only as evidenced by the almost countless entrances and exits of personages, but also by all of the stage properties which have such an important function throughout Arrabal’s work.

Critics are quick to point out several curious juxtapositions which typify the work of this playwright, among them the childlike mentality of sexually mature individuals, the sadistic cruelty of morally innocent creatures, the castigating actions of the victim. More than merely paradoxical juxta-positions, however, these dichotomies constitute the by-products of a circular structure whose significance lies in the playwright’s announced intention to portray with clarity the chaos of man’s existence. At times, this structure will define the confused configurations of organized justice and religion, at other times the violent bestiality of love, and at others the inane impersonality of war. Here, in La Bicyclette du Condamné, the structure conveys the inchoate identification between freedom and condemnation. It is by means of a systematic analysis of the circular structure in Arrabal’s work that meaning will become clear in this and other pieces which at first glance may appear to be meaningless games. It is also by virtue of understanding this dramatic structure that the critic can avoid the contention that Arrabal is « more a visionary than a dramatist » who should move in the direction of « the creation of a series of ever-moving tableaux, » since the static quality does not suit his work. Neither tableaux nor the static are Arrabal’s technique, and in his circularity lies one of his claims to originality.

Briefly, in La Bicyclette du Condamné, the action takes place around the piano of Viloro, whose principal goal seems to be to play the C-scale perfectly, despite an unexplained prohibition against his playing by Paso and Two Men. Viloro’s efforts, sometimes successful but more often fruitless, are constantly interrupted by the alternating appearances of his beloved Tasla on her bicycle dragging a caged Paso to his torturers and executioners, and of an inexplicably free Paso in the company of Two Men, who subject Viloro to progressively more confining punishments for his transgression of their prohibition against piano-playing. (Never is it suggested that there exists any logical reason for the prohibition nor for Paso’s imprisonment and Tasla’s inescapable duty to transport condemned men.) Interspersed among these interruptions are erotic episodes where-in Tasla engages in pursuits of and escapes from Paso and the Two Men. The play ends in the death, not of Paso, but of Viloro at the hands of Paso, followed by echoes of the same mocking laughter and piano scales with which the curtain opened (figuratively speaking, since Arrabal’s plays seldom open with a curtain). Throughout the action, the spectator has been confronted by first a free Viloro and an apparently imprisoned Paso, then by a free Paso and a confined Viloro, then again by the imprisoned Paso and free Viloro, alternating appearances which recur ad infinitum. Since the play’s final scene reproduces in acoustical and symbolic form one of the play’s recurrent episodes, the action comes full circle back to what may be termed a beginning in linear structure but is merely one of the cyclic phases in this play’s circular structure.

Thus, the essential blocks of action are seen to follow a circular arrangement, since they offer a repetitive rhythm involving apparently condemned individuals…. [The] repetitive pattern is not truly terminated, but rather is brought back to the beginning, where the same question confronts the spectator: Who has been condemned to what? Paso, apparently doomed in the beginning and at significant intervals throughout the play, emerges free of his imprisonment in the end. Viloro, apparently free at the outset and at regular points throughout the play, ultimately replaces the caged man. The implication of the basic problem of the condemned man’s identification, then, extends to include the question of freedom, and the circular structure of the work leaves the spectator with the somewhat inconclusive awareness that the burden of freedom is essentially the same kind of punishment as that of condemnation.

Furthermore, within … blocks of action …, equally precise circularity is evident, and it is here that objects and sounds are used to great effect in support of the play’s basic structure. As the play opens, Viloro, alone on stage, futilely attempts to pick out a C-scale on his piano, but his efforts evoke only laughter from Two Men behind a wall and then from Paso. This motif of the musical scale, then, with its repetitive return to the beginning, provides the acoustical counterpart of the structure which configures the entire play. In addition, the rhythmic abcpattern of this first sub-block of action (Viloro alone playing scales—appearance of Two Men—appearance of Paso) is repeated after each of Tasla’s trips with the caged Paso. Just as Viloro always returns to his piano scales, the action of the play always returns to the isolated Viloro subjected to his tormentors.

This acoustical pattern shows a significant refinement in its relationship to those larger blocks of action wherein Viloro is subjected to progressively more restrictive punishments…. [The] acoustical phase of the play’s circular structure echoes the fundamental identification of freedom with condemnation, for it is precisely during his periods of greatest confinement and restriction that Viloro demonstrates his greatest freedom to play the piano as he wishes with the success he strives for, unencumbered by timidity and ridicule.

Objects also carry out the cyclical pattern of the work. In addition to repeated appearances of the bicycle and wheeled cage, whose very construction exhibits circularity and which travel on a circuitous path, Tasla and Viloro exchange the same gifts over and over again—a balloon, a chamber pot, and an infantile song composed first by Viloro and then Tasla. They day-dream in circles, longing for the day when Tasla will be free of carting condemned men around and Viloro will be left in peace to play the piano as much as he likes. Ironically, though, their dreams also include a repetition of their present activities, for Tasla promises to tow Viloro in her cage, and he promises to relieve her on the bicycle occasionally while she sits in the cage. Here again, the inextricable link between Viloro and Paso, freedom and condemnation, is maintained, as it also is suggested in the promise Viloro extracts from Tasla to send him a kiss for every lash applied to Paso in the torture chamber.

Even the bicycle exhibits this same relationship to the freedom-condemnation conundrum, for Tasla somehow is condemned to carry condemned men by means of her bicycle. Yet, as she yearns for the day when she will be free, she dreams in terms of that same bicycle. Similar confusion exists in regard to the cage itself, which in the action of the play is a prison but in Viloro’s dream is equated with freedom. Thus, the use of these wheeled conveyances to remove his body following his final punishment is in some way, not only a comdemnation, but a deliverance into the freedom he and Tasla had dreamed of.

The play, then, reflects the human chaos as it pertains to the dilemma of freedom and condemnation, yet that reflection is constructed upon an intricately precise labyrinth of concentric circles extending from purely physical appearances and objects, through acoustical realms, until finally it comprises the very human condition itself. Conspicuously, the dialogue provides little clarification of the play’s apparent disorder, and in this regard, Arrabal’s insistence upon the precision of the mise en scène becomes more significant, for the result of that negation of dialogue as the tool by which chaos is rigorously ordered into ceremonial clarity is to demand of both audience and critic a strict attention to the non-linguistic structure of this play and all of Arrabal’s work. (pp. 205-09)

Beverly J. Delong-Tonelli, in Modern Drama