J’ai beaucoup vu, analysé et conversé avec Viktor Kortchnoï.

Pendant les 31 ans de ma chronique hebdomadaire dans l’Express.

J’ai assisté à tous ses championnats du monde.

Le lendemain de sa dissidence, de son « destierro » j’ai été chez lui à Genève « en écrivain ». Il m’a salué:

– Vous êtes les premier journaliste qui ose …

Réconforté par cette promotion j’ai parle avec lui du divin et de l’humain.

Je me souviens de certains de ses inattendus « arrabalesques »:

“Aux échecs il ne sert à rien de penser: il faut réfléchir avant ».

*

“Quand je suis abattu, je me fais moi-même échec et mat. »

*

“Pour mémoriser une ouverture la meilleure manière c’est de ne pas l’oublier »

*

“Un prix de beauté aux échecs peut être juste si le jury se trompe.

*

“Je joue aux échecs comme si ma partie était analysée par mon ennemi.

[“En ajedrez de nada sirve pensar hay que reflexionar antes”.

*

“Cuando me siento abatido me doy jaque mate a mí mismo.”

*

“Memorizar una apertura es la mejor manera para no olvidarla.”

*

“Un premio de belleza en ajedrez puede ser exacto cuando el jurado se confunde”.

*

“Juego al ajedrez como si mi partida fuera a analizarla mi enemigo.”]

***

Jouer sa vie Réalisation : Gilles Carle [Qué., 1982, 80′] avec Fernando Arrabal, Viktor Kortchnoï et Bobby Fischer. Fernando Arrabal analyse un tournoi international d’échecs où sont évoqués tour à tour le spectacle, l’histoire et les stratégies propres à ce jeu. Défilent devant la caméra Karpov, Fischer, Korchnoï trois des plus grands joueurs de l’histoire, au cours d’un jeu de duels à la manière de la tradition des westerns.

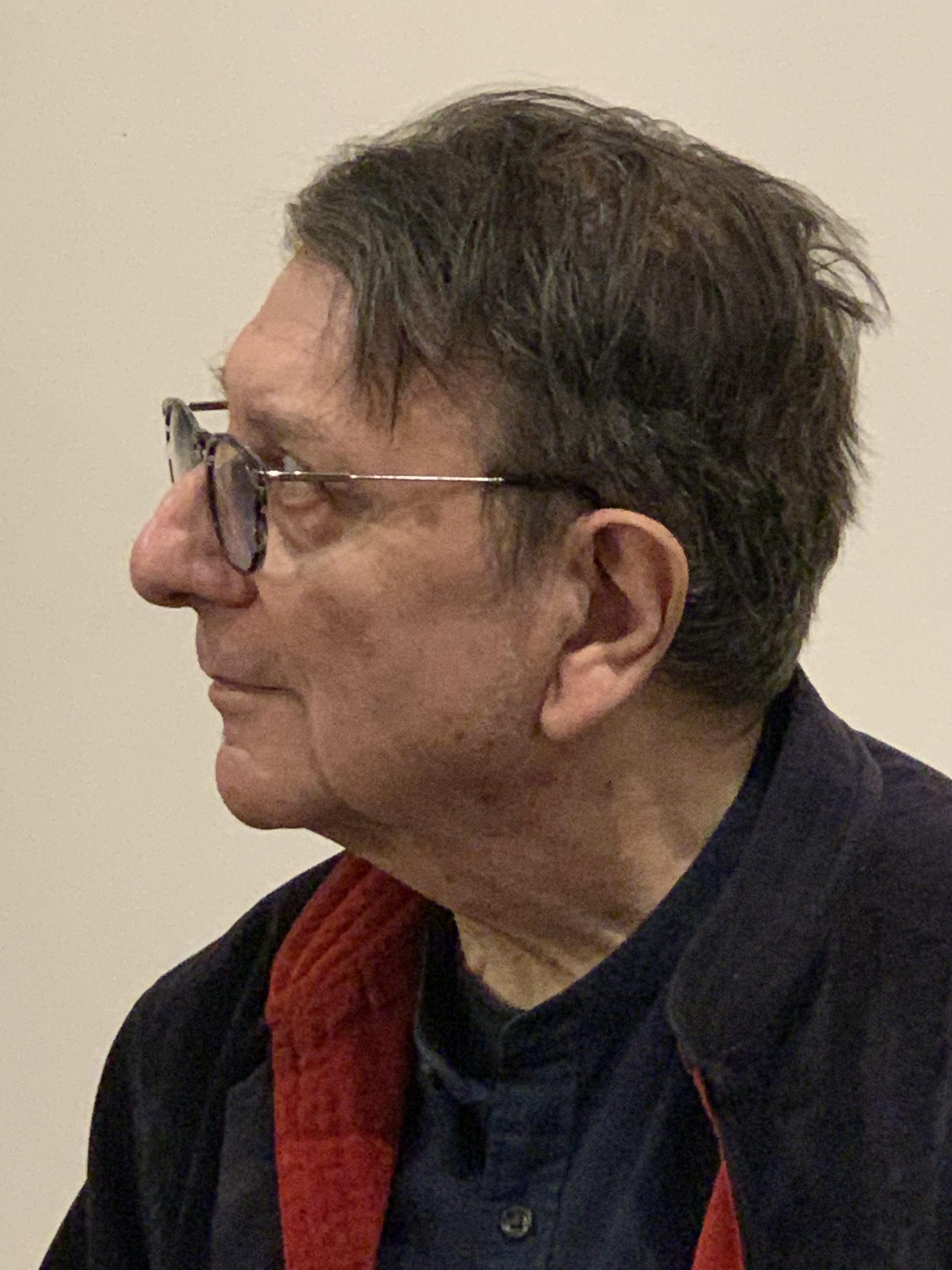

Viktor Lvovitch Kortchnoï est né le 23 mars 1931 à Leningrad, en URSS, est mort le 6 juin 2016. Il obtint l’asile politique de la Suisse en 1978, puis la nationalité suisse en 1992. Après sa défection de l’Union soviétique en 1976, Kortchnoï disputa deux matchs de championnat du monde d’échecs — en 1978 et en 1981 — contre le numéro un soviétique Anatoli Karpov, de vingt ans son cadet. Grand maître international depuis 1956, Kortchnoï fut pendant plus de trente ans un des dix meilleurs joueurs du monde.

Bien qu’il n’a jamais été champion du monde, Kortchnoï est un joueur au palmarès des plus prestigieux, connu pour sa ténacité et sa constante volonté de vaincre. Il fut candidat au championnat du monde en un nombre record de dix occasions : en 1962, puis, sans interruption, de 1968 à 1991. Quatre fois finaliste du cycle des candidats, il remporta la finale contre Boris Spassky en 1977-1978 et face à Robert Hübner en 1980-1981. ( https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viktor_Kortchno%C3%AF )

Viktor Korchnoï:

Le Lion a cessé de rugir. Il était né à Leningrad, actuel Saint-Pétersbourg, le 23 mars 1931. C’est dans le grand fief russe des échecs qu’il remporta ses premiers succès. Sacré champion de Leningrad junior en 1946, il regrettera toute sa vie que la guerre lui ait « volé » quatre de ses premières années de formation. Souvent, il dira que c’est peut-être ce « petit plus » qui lui a manqué pour devenir Champion du Monde. C’est le seul titre qu’il n’a jamais réussi à inscrire à son palmarès. Il a affronté et battu tant de détenteurs de la couronne suprême, en commençant par Botvinnik.

Ses deux matchs contre Karpov en 1978 et 1981 sont rentrés dans la légende. Il n’était plus un héros de l’URSS, mais un joueur apatride, avant de défendre les couleurs de la Suisse. Seul, il a lutté contre un régime, soutenant Bobby Fischer contre ses collègues GMI du puissant Comité des Sports de l’Union soviétique. C’était au temps de la guerre froide. Il était devenu l’homme à abattre. En 2006, il se para enfin de la couronne mondiale. C’était en vétéran. Il avait 75 ans. Quel juste retour des choses ! On le surnommait« Viktor le Terrible ». C’était un guerrier au caractère parfois irascible. Ses colères sont fameuses. Elles ont aussi écrit l’histoire. C’était surtout l’un des plus grands champions qu’ait connu ce jeu. Juste un Roi sans couronne. Il restera sans doute comme le plus fort Challenger jamais sacré de tous les temps. Adieu, Viktor Korchnoï ! (Europe-Echecs)

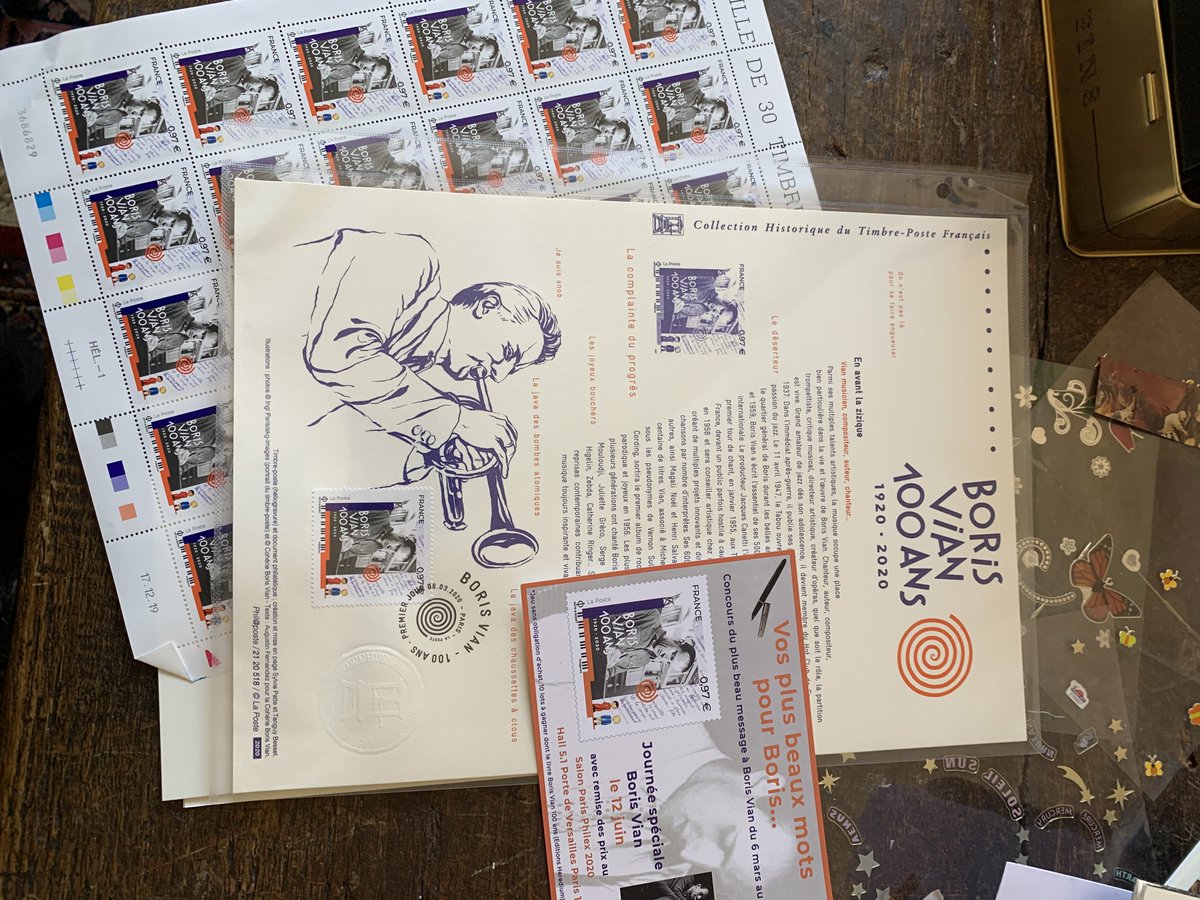

Viktor Korchnoi – 23 March 1931 – 6 June 2016 By Frederic Friedel: CHESSBASE MAGAZINE EXTRA NEWSSHOPDATABASEPLAYCHESS.

He was one of the truly great chess players, a legend. He played in three matches that produced the World Champion, but in each case lost to Anatoly Karpov. It made him the strongest player never to have won the title. In 1976 he defected from the Soviet Union and took up residence in Switzerland, where he continued to be active into his eighties in spite of a stroke. Now he has gone and leaves a grieving chess community.

Viktor Korchnoi was a professional chess player, one of the strongest grandmasters in the world, twice World Championship challenger, the strongest player never to have won the title. He was also, in recent years, the the oldest active grandmaster on the tournament circuit.

Viktor Lvovich Korchnoi was born on 23 March 1931 in Leningrad, Soviet Union, to a Jewish father and a Catholic mother. He learned to play chess from his father at the age of five. He graduated from Leningrad State University with a major in history.

In 1974 Korchnoi lost the Candidates final to Karpov, who became the Challenger and was declared world champion when Bobby Fischer refused to defend his title in 1975. After that Korchnoi won two consecutive Candidates cycles to qualify for World Championship matches against Karpov, in 1978 and 1981. He lost both. In total Viktor Korchnoi playind in ten Candidate tournaments (1962, 1968, 1971, 1974, 1977, 1980, 1983, 1985, 1988 and 1991). He was also a four-time champion of the Soviet Union. In September 2006, he won the World Senior Chess Championship.

In 1974 it became clear that a campaign was under way in the USSR to promote Karpov over Korchnoi. The central authorities prevented him from playing international tournaments, or even in Estonia, which was part of the Soviet Union. He was Korchnoi was allowed to play in the tough 1976 IBM Amsterdam 16-player round robin, probably in order to prove that he was not so strong, and that Karpov was a worthy World Champion. Korchnoi was the joint winner of the tournament along with Tony Miles, both scoring 9.5/15 points.

At the end of the tournament, Korchnoi famously asked Miles to spell « political asylum » for him. He became the first strong Soviet grandmaster to defect from the Soviet Union. He had to leave his wife and son behind. He resided in the Netherlands for some time, moved to West Germany and then eventually settled in Switzerland by in 1978. He continued to play chess, and in 2009 became the oldest player ever to win a national championship, when he won the Swiss championship at age 78.

In 2012 he suffered a stroke and the general opinion was that he would never play competitive chess again. Still he continued to give simultaneous exhibitions and in 2015, bound to a wheelchair, he played a match against German GM Wolfgang Uhlmann. He attended the 2016 Zurich Chess Challenge earlier this year, but was not able to play anything himself.

I got to know Viktor Lvovich shortly after his defection, when he visited Hamburg. We got on well, shared a slightly diviant sense of humour, with myself enjoying his sometimes caustic and rude remarks. He always spoke to me in German, even if I started the conversation in English.

At some stage I got to know his wife Petra, who quickly became one of my best friends in the chess world. I have always sought and enjoying her company, joking and flirting. I know her harrowing life story, how her life was interrupted by captivity and a decade-long incarceration in a Soviet concentration camp in the Arctic Circle immediately after the war. Her’s is a life story that must be told – and will be sometime in the future.

When I met Viktor and Petra in Zurich in February this year, he was frailer than I had ever seen him before. When he saw me he simply smiled and shrugged his shoulders: « What you gonna do? » was the meaning of that shrug. Petra, who is a couple of years older, was also uncharacteristically shaky, and I found myself helping her to her armchair or through doors. When I commented on Victor’s feebleness she said to me: « I only hope he dies before me, Frederic. » « Why? » I protested. « Because I do not know who could care for him if I am gone. »

There will me many stories following this somewhat rushed eulogy. Our editors are already working on them. I myself could go on all night, but will restrict myself to pointing our readers to a few of the great number of article we have published on this great man over the years.

2011, Viktor Korchnoi turned 80. There was a week of celebrations, held mainly in Zurich, which is not far from where Viktor Lvovich and his wife Petra live. The celebrations were kicked things off with a clock simul by Korchnoi, and then a gala dinner in his honour. Guests included Mark Taimanov and Garry Kasparov.

Above you see the man for whose 80th birthday all this had been organised, already hard at work himself. Viktor Korchnoi was playing a clock handicap simultaneous exhibition against ten talented youngsters from the Swiss Youth team. Absolutely amazing.

Incidentally, I came down to the Festival Hall, where the simul was under way, with a message from another guest: if the eighty-year-old simultaneous master was overcome with fatigue he could enlist the assistance of an unrated player who was willing to jump in for him, for a move or two. However, Viktor refused: he would do the job by himself. But thank you very kindly for the offer, Garry Kimovich.

And here are some picture of two great chess legends: below we see Viktor in animated conversation with 85-year-old Mark Taimanov, who had come to Zurich for the celebrations.

In 2005, at the age of 73, Viktor visited us in Hamburg to record two fascinating DVDs on a life devoted to chess – a career that spanned more than five decades and six generations of opponents.

At the time, when we decided to make the DVDs, I was a bit nervous. Even in normal conversation Viktor Lvovich was always very intense. No small talk, any question or remark could elicit a profound, witty, or caustic response. And since this was all done in a foreign language, and since he was never willing to compromise his high standard of erudition, the conversation was sometimes ponderous. You had to wait for many seconds while he thought, he would pause mid-sentence and search for a word. He would even go back and correct a previous sentence when a better expression has occurred to him.

Viktor Kortchnoi in Studio ChessBase in Hamburg

How would this play out in a video recording, where the speaker is expected to be fluid and eloquent? It was with some trepidation that I took a seat behind the camera in our recording session in the Hamburg “Studio ChessBase” (where Garry Kasparov and others have made a series of wonderful training CDs). Viktor had spent half an hour receiving technical instructions, we had given him IM Oliver Reeh, just out of the picture, to help with the computer operation when he needed it, and he had briefly flipped through his new autobiography “Mein Leben für das Schach” (My Life for Chess, Olms Verlag, 2004). Light, camera, and action!

It was unlike anything I had expected. Viktor Lvovich was completely at ease, spoke powerfully, interspacing profundity with humorous moments, objective chess analysis with scintillating historical narrative. The pauses were there, the struggle for the mot juste. But he used it to dramatic effect. You could feel the intensity, the uncompromising need to say exactly what he was thinking. Let me give you a couple of impressions, literal transcriptions, which of course fail to convey the verbal and facial eloquence, the sly grins and wide-eyed stares. But it will give you a rough idea.

1967. In that year the Soviet state celebrated fifty years of, more or less, its existence. It was the fifty year’s anniversary of the so-called October Socialist Revolution. In order to commemorate this day they organised two big international tournaments – one in Moscow, one in Leningrad. Well, there were even rumours that Bobby Fischer was ready, was eager to take part in one of these tournaments, without any extra fee. Just to play. There were rumours. But the Soviet authorities thought it over and decided not to allow him to come to the Soviet Union. “What the hell would happen if an American citizen would win the tournament commemorated to the fiftieth anniversary of the Soviet state?” No, sorry, so the tournaments were played, the stronger one, in Moscow, was won by Leonid Stein, and the weaker one in Leningrad was won by me, in a fight with Grandmaster Kholmov, who was second. So I won several interesting games, and I am going to show you one of them.

[Kortchnoi starts to replay his white game against Mijo Udovcic, which begins 1.d4 e6 2.e4]

Well, some time ago the then world champion Mikhail Botvinnik said that a young player had to arrange his opening repertoire in a way that he would never have to play against himself. What does it mean? It means that if I play the Grunfeld with black against d4 and the French Defence against e4, I should not play against the French myself. Somehow I had to avoid openings which I play myself. But I got tired of playing closed openings and decided to take the challenge. The guy wanted to play the French against me, I take it! But if possible I would avoid the most modern lines.