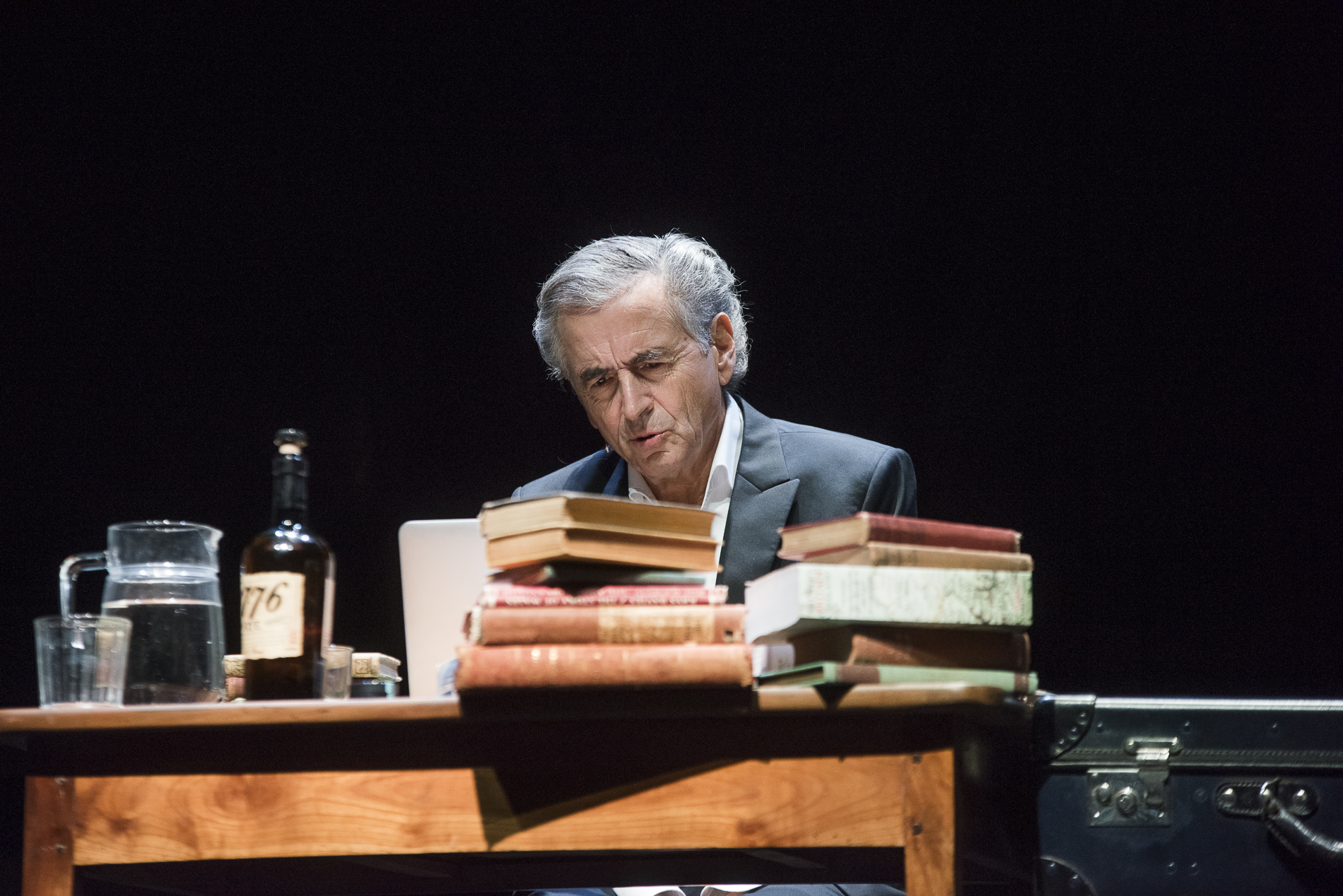

France’s most public intellectual sank into a bathtub, while fully clothed in a bespoke suit, onstage in a one-night-only theatrical production to make a plea for Britain to reconsider its decision to leave the European Union.

“Please, please remain”, Bernard-Henri Lévy begged the audience at Cadogan Hall in Chelsea, a posh London neighborhood, where the silver-maned provocateur was greeted with rapturous applause.

“This damn Brexit, if they go through with it, will be a win for the hard right over the soft right. For the radical left over the liberal left!” Lévy was just getting started.

“All over the U.K., it will be the revenge of fusty Britain over the Britain that is open and in touch with its glorious past. It will be the consecration, in London, of Trump and Putin. Of drunken hooligans and illiterate bullheaded neo-nationalists,” he said.

Two years after the British decided to leave the union, as Prime Minister Theresa May struggles to forge a deal that her squabbling cabinet, skeptical Parliament and Brussels might all approve, there remains a sliver of hope — or, perhaps, a delusion — among some Anglophilic Europeans that Britain might yet be persuaded to forget this nasty Brexit business and stay put.

There is the slimmest chance Brexit might be put to a second referendum and that a deal might be voted down. Polls in Britain show a shift of a few points against Brexit since June 2016. Members of Parliament are also agitating to have an up-or-down vote on May’s final Brexit plan. There is great passion for this. On Tuesday, Phillip Lee, a Tory justice minister who voted against Brexit in the referendum, surprised many when he resigned from the government to speak out against May’s plan to leave the bloc. He was adamant that lawmakers get a vote on the final plan.

Yet the notion that a do-over on Brexit would come about because of the pleas of a French intellectual — or Brussels Eurocrats or wealthy outsiders or European newspaper columnists — seems quixotic at best.

Few can match Lévy’s flair. But his sentiments are shared elsewhere in Europe.

“The entire saga has become one frivolous political experiment”, German columnist Bernd Riegert wrote for Deutsche Welle. “It would be better to just forget Brexit and do away with this nonsense… There is still a year to call off the divorce.”

European Council President Donald Tusk has confessed that he is gutted by Britain’s decision to exit the bloc — and he has urged that it is not too late to turn back. “We, here on the continent, haven’t had a change of heart. Our hearts are still open to you”, he said in January.

Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, echoed that message: “Our door still remains open, and I hope that will be heard clearly in London.”

Former British prime minister Tony Blair has encouraged these entreaties. Speaking in Brussels in March, he told European leaders that they “share the responsibility to lead us out of the Brexit cul-de-sac and find a path to preserve European unity.”

One of the most prominent outsider-ish, anti-Brexit campaigns in Britain kicked off Friday, calling for a “people’s vote” on the final deal negotiated between Brussels and London, with an option of staying in the union. This movement, calling itself Best for Britain, is backed by Hungarian American financier George Soros, who has donated about $1 million, or 20 percent, of the group’s total funding.

“Since Brexit is a lose-lose proposition, it follows that a parliamentary vote to stop Brexit would be its opposite”, Soros wrote for the Mail on Sunday newspaper. He exhorted British voters to push their lawmakers, “to give them the courage to rebel against the party leadership, and the electorate needs to be motivated not just to vote but to take an active role in politics.”

Best for Britain chairman Mark Malloch-Brown told reporters in London on Friday that between 40 and 50 lawmakers have said they will support a second referendum — nowhere near the votes needed in the 650-member House of Commons to stop this train, which long ago left the station.

Meanwhile, the Soros support for Best for Britain has not gone down so well with Brexiteers, who say the entire point of Brexit is for Britain to take back control of its destiny from the continentals.

“Butt out, Mr. Soros. You can keep your tainted money”, ran a front-page headline in the Daily Mail, which backed Brexit.

John Longworth, co-chairman of pro-Brexit group Leave Means Leave, was quoted in the Sun newspaper as saying, “They are insulting British voters and our proud British democracy.”

Soros defended his efforts, saying he is motivated by a love for Britain. (He was educated at the London School of Economics and has lived and done business in Britain.)

Lévy’s play, “Last Exit Before Brexit”, also received a proper drubbing.

“The notion that a Frenchman standing on a stage in Chelsea and berating the British could change people’s minds about Brexit was always far-fetched”, the Economist reported. “But BHL’s performance was even odder than this suggests.”

The magazine archly observed that there was more French and German than English spoken in the theater bar.

A journalist and writer, Lévy has recently involved himself in international affairs, notably in France’s 2011 intervention in Libya, when he was among the key influences on then-President Nicolas Sarkozy.

Le Monde, for one, has neither forgotten nor forgiven. Its report on Lévy’s London play opened with: “After having ‘saved’ Bosnia and Libya, will ‘BHL’ save the United Kingdom from Brexit?”

For Lévy, as for many other continental intellectuals, Brexit is not so much about Britain as it is about Europe, a political project whose woes have only continued since Britain opted to leave. “Last Exit Before Brexit” hardly celebrates the E.U.; it confronts Brussels head on for what Lévy perceives as weakness and facelessness that allowed Brexit to happen.

Although the political center has proved durable in post-Brexit elections in France, the Netherlands and Germany, a coalition of right-wing populists has now assumed power in Italy, a founding member state of the E.U. and its third-largest economy.

Meanwhile, the leaders of Hungary and Poland have openly defied Brussels and the values it champions, essentially with impunity, attacking freedom of the press and the independence of the judiciary.

According to a YouGov poll conducted in March, a clear majority in Germany wants Britain to stay in the E.U., while France is more divided on whether the Brits should stay or go.

Although some in France have seen Brexit as an opportunity for an amplified French voice in European politics — as well as a chance for Paris to replace London as Europe’s financial capital — the dominant view within the French political establishment is one of resignation and regret, said Dominique Moïsi, a foreign policy expert at the Institut Montaigne, a Paris-based think tank, and an informal adviser to the Macron campaign.

“What prevails, specifically with regard to the security and defense concern, is the idea of ‘what a pity, what a shame.’ The British are leaving Europe at a time when the Americans are leaving the world, when Europe is more necessary than ever. We’ll have to make do,” he said.

When asked in January by the BBC whether Brexit was sure to progress, French President Emmanuel Macron threw up his hands. “It’s on your own,” he said. “It depends on you.”

McAuley reported from Paris. Karla Adam in London contributed to this report.