It was, said audience member Anne von Bennigsen afterwards, “really very French. Fascinating, but just not very… practical. Nothing particularly concrete. Still, he’s a French intellectual, I suppose. And that’s how he came across.”

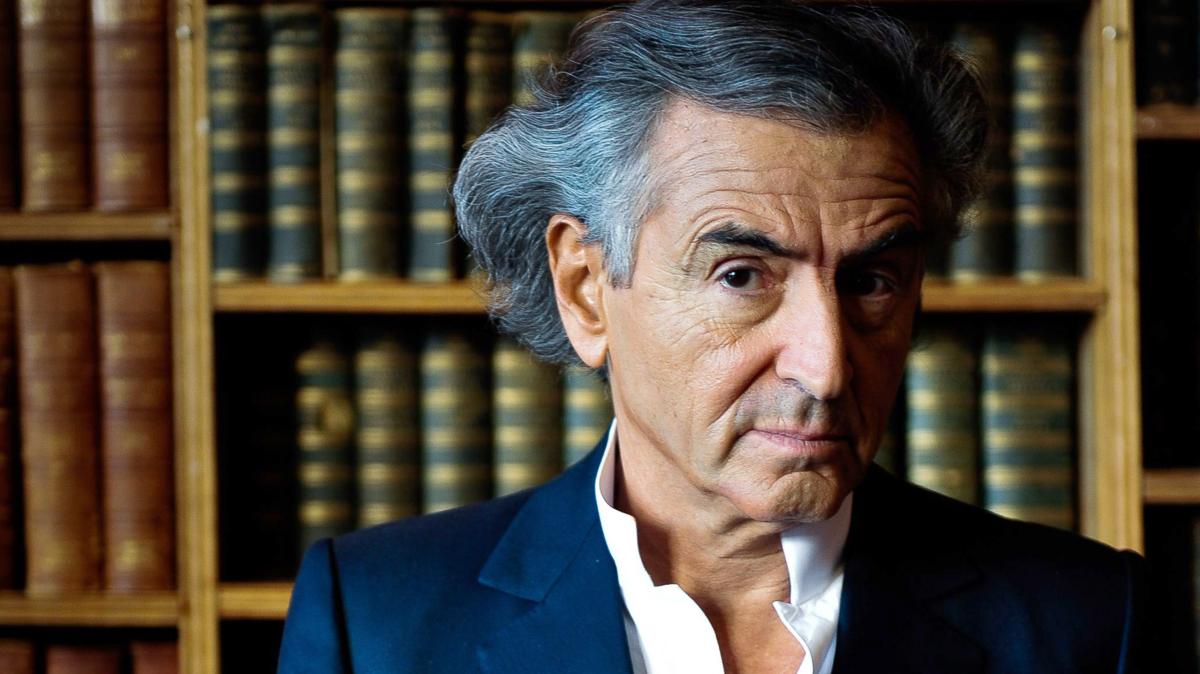

Poking fun at Bernard-Henri Lévy may be a national sport in France, but a bemused audience of nearly 1,000 packed Cadogan Hall in London on Monday to hear the 69-year-old philosopher plead with Britain to remain in Europe, in English.

BHL, as he is almost always known, has been a fixture on France’s TV screens for decades, the flamboyance of his intellect matched only by the unshakability of his self-confidence and the whiteness of his carefully unbuttoned shirts.

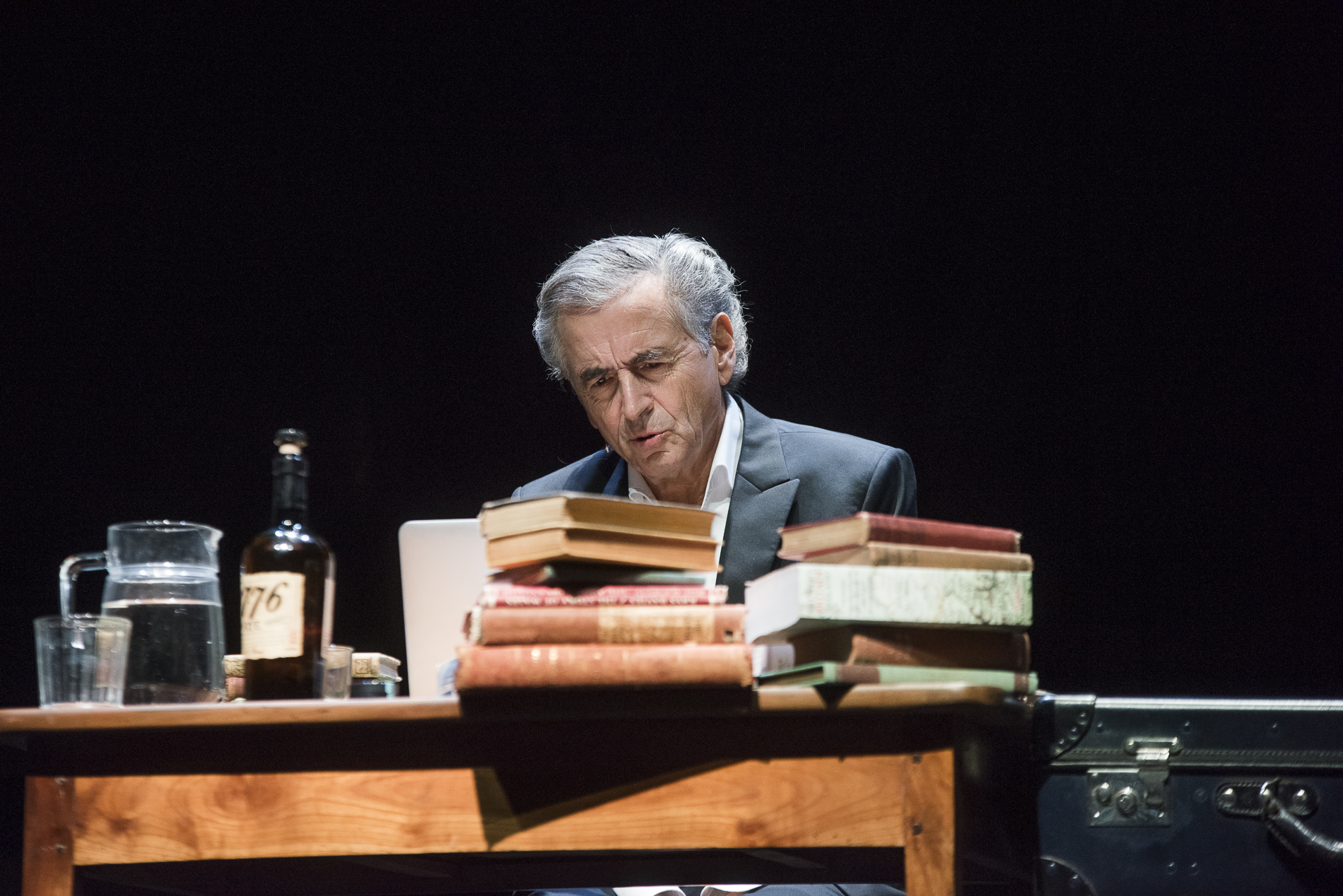

His one-man play Last Exit Before Brexit has been updated, adapted and translated from an earlier work, Hôtel Europe (which premiered in Sarajevo in 2014), to take account of Britain’s decision to leave the EU. It left many unfamiliar with the showman-philosopher somewhat nonplussed.

“He’s a caricature of the French intellectual”, said another audience member. “Fantastic to see somebody take themselves so seriously,” said his colleague. “Nobody in this country would ever do that.”

But for all its complex, lofty and undeniably Gallic bent, the play – a two-hour stream-of-consciousness monologue by a writer struggling in his hotel room to pen a Brexit conference speech about the tattered but still indispensable European dream – contained plenty of red meat.

“It’s a fact”, Lévy declared from the stage, calling John Locke, Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes and Karl Popper as his witnesses. “Without Europe, Great Britain will become Little England, and without Great Britain, Europe will crumble.”

For if Europe’s economy is German and its politics French, he said, its ideology is fundamentally British: “European liberalism is an English idea; you cannot truly be a liberal without admitting that the software of Europe is English.”

Under attack from within by “mediocrity, bitterness and cowardice”, the European ideal risks “knockout” from Brexit, he said: the “inventors of modern democracy” have somehow confused “the people with the mob, the hatchet of the referendum with the wisdom of the agora, a national rebirth with a plunge into the void.”

If Brexit is ever completed, it will be “a win for the hard right over the soft right, and for the radical left over the liberal left,” he lamented. “The revenge of fusty Britain over open Britain. The triumph of ignorance over knowledge, of the mindless over the mindful, of pettiness over greatness.”

Among Great Britons now being “shrunk” by Brexit, which he called “not a return to the high seas but a pathetic retreat to a sandcastle”, he named Nelson, Stevenson, Byron, Hillary, Shackleton, Florence Nightingale, Lawrence of Arabia, Orwell, Bowie, James Bond, Stephen Hawking and Monty Python – as well as “Alexander Fleming, who saved half humanity, and Paul McCartney, who charmed the other half.”

As for Europe, its salvation must lie in “the return of courage, and the powerful chemistry of dreams” – and in a new European commission, headed by Robert Schuman and with John Locke at human rights, Diderot in education, Goethe at culture, Rosa Luxemburg in defence, Pussy Riot at women’s rights, Isaac Newton at research and Bob Geldof running charitable causes.

“Please, please remain”, he concluded. “The long march begins tonight. Last exit before Brexit!” It was all a bit much for some, but Bogdan Wolf, a Polish-born psychoanalyst in Britain for 40 years who described Brexit as “an absolute disaster … part of a fascist resurrection”, was delighted.

“What came out of it for me was precisely the idea of the idea”, he said. “Europe is not about pragmatism, negotiations, deals. It’s an idea of how to speak to one another, while disagreeing with one another. That’s why it matters.”