The Automobile Graveyard | Teatro Dallas.

The Automobile Graveyard | Teatro Dallas.

Top Gear. At Teatro Dallas, Fernando Arrabal’s The Automobile Graveyard is timely and important theatre.

Dallas—The Automobile Graveyard . « El cementerio de automóviles » (1956) de Fernando Arrabal (Melilla,1932) tiene una historia única. Obra representada a lo largo de estos últimos 60 años por los más ilustres actores, directores y escenarios de teatro en los cinco continentes.

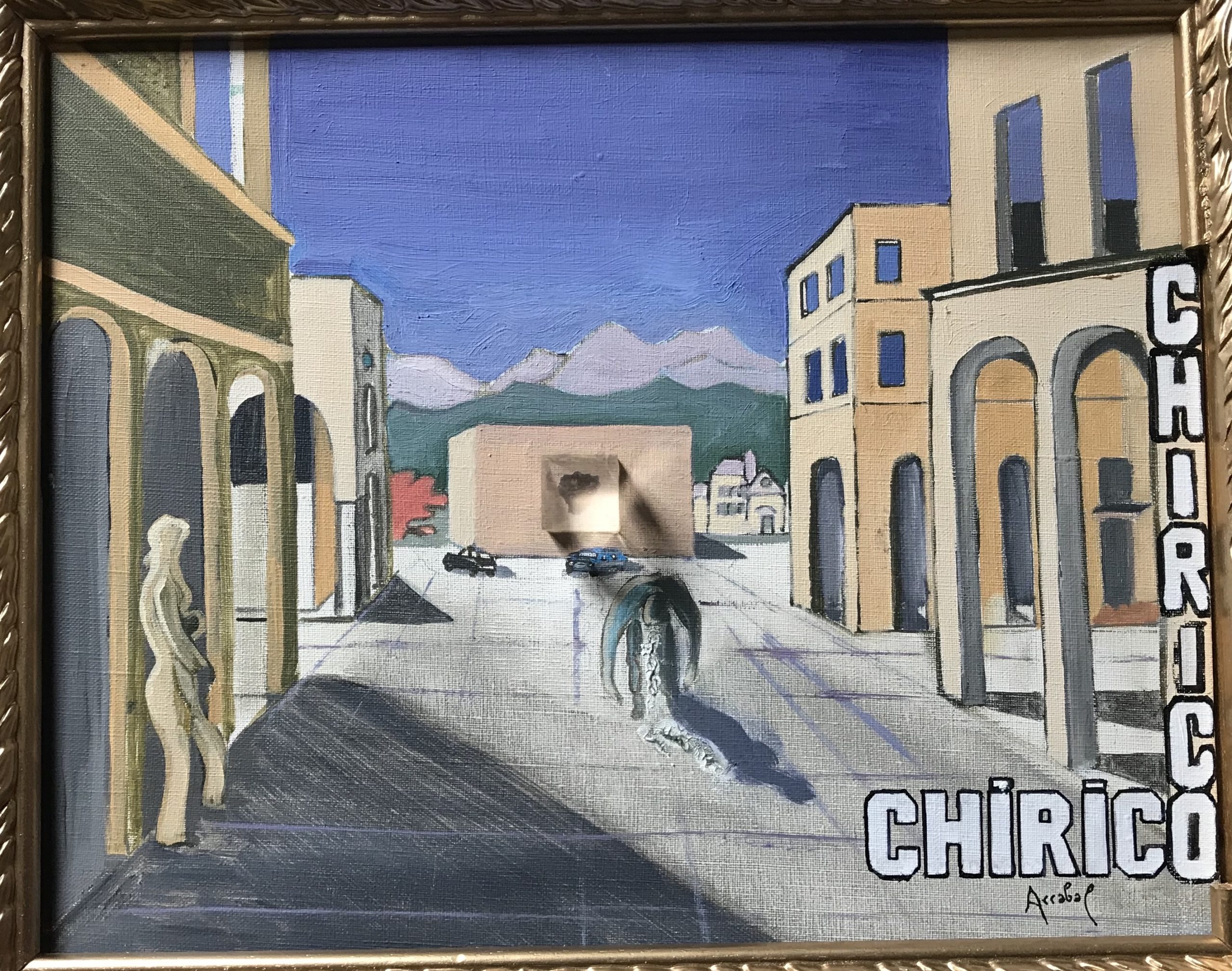

Dallas — The Automobile Graveyard (El cementerio de los automóbiles), written by Fernando Arrabal (1956), has an illustrious background. A piece written during General Francisco Franco, the Spanish dictator whose iron hand rule extended from 1939 to his death in 1975, it was originally banned by the government censors due to its “grotesque content and possible anti-Catholic” hostilities. The production now at Teatro Dallas, translated by Richard Howard and directed by Cora Cardona for its Texas premiere, and does not alter the hypertext’s intent to shock, entertain and sometimes repulse. A clear and newly introduced element on the original text is the presence of ICE roundups and the arbitrary shooting of unarmed people by police officers.

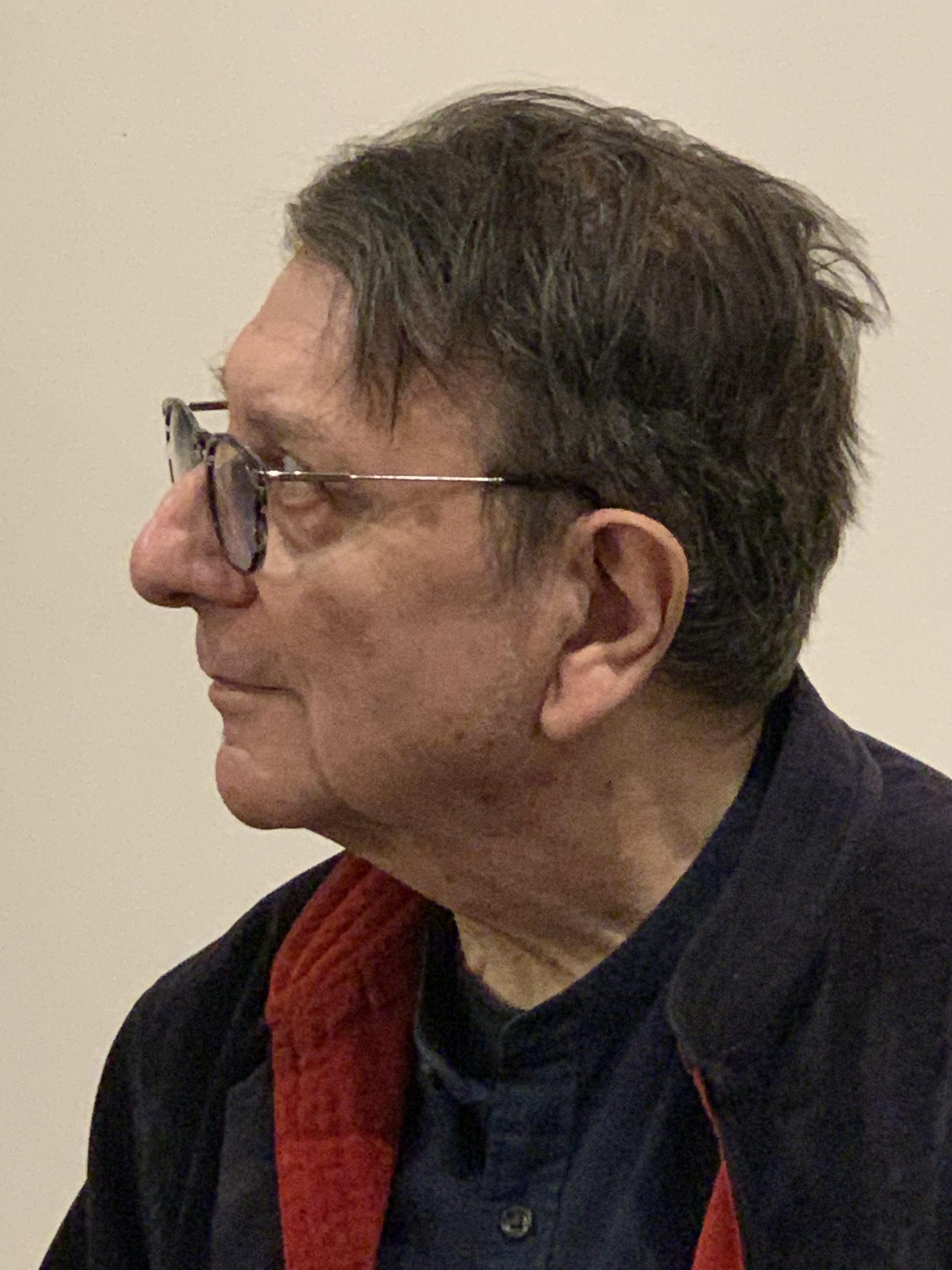

Arrabal, himself born in Spain, left that country in a self-imposed exile to France since 1955. By all accounts, this piece pushes the envelope, even within the various European avant-garde traditions from which it hails (the grotesque, theatre of cruelty and the absurd). His work is quite honored within the French and Spanish academies. His politics lean towards the European anarchist trend of cultural production.

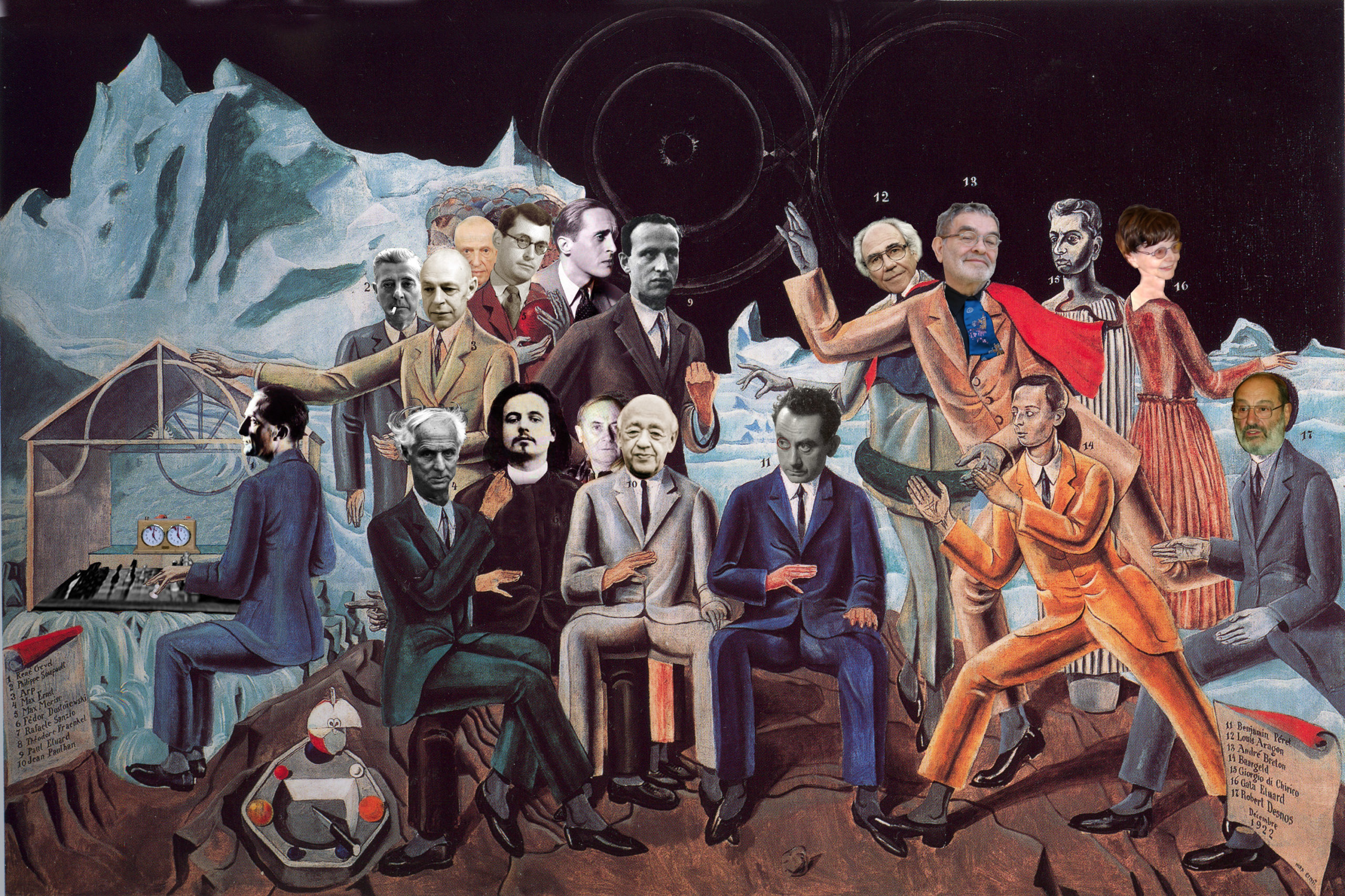

In 1962 Arrabal co-founded the Panic Movement (Teatro Pánico) with Chilean-French playwright, Alejandro Jodorowsky, a filmmaker and someone who had a great influence on Cardona and many other Latin American theatremakers, and French writer and illustrator Roland Topor. This aesthetic was influenced by Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty. Since 1990, Arrabal has held the honorary title of « Transcendent Satrape » in the College of ’Pataphysics (Collège de ’Pataphysique), founded in 1948 in Paris, is “a society committed to learned and inutilious research” (the neologism “inutilious” is synonymous with “useless”). You get the drift.

These artists have a sense of humor bent on deconstructing artistic culture’s own conceits. This group was founded in homage to the French author Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), author of the landmark Ubu Roi (1896), the first absurdist play in the Western theatrical canon. Other members of the iconoclastic Collège de ’Pataphysique and of the Transcendent Satrapes are internationally known artists such as Camilo José Cela, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, M. C. Escher, Eugène Ionesco, Man Ray, The Marx Brothers, Joan Miró, Umberto Eco and Dario Fo, among others. Indeed, Arrabal stands shoulder to shoulder with the most European avant-garde and innovative, creative minds of the 20th century. Why he may not be well-known within the United States points to our penchant towards realistic, commercial theatre.

Teatro Dallas continues to amaze with the ways in which it can transform a small black box space. This time scenic designer Nick Brethauer creates four spaces with real, junkyard automobile parts and five acting spaces on a multilevel set. Lighting by Jeff Hurst has a playful role illuminating the shenanigans that go on inside the automobiles, with costumes by Michael Robinson.

Within this graveyard, persons inhabit each of the abandoned cars. Persons, as broken and disposable wastes as the cars, create an ambiance that mixes cruelty with the absurd in an intentionally dissonant way. Violence is rampart as Dilla (Monica Pérez) is both prostituted and beaten at one point by Milos (Carlos Navarro), only to inexplicably rise as the dominatrix in another. Milos, the hotel like attendant of the graveyard, exerts his power over her as he physically and emotionally abuses Dilla, only to later emerge as himself the victim of her vengeance.

On the other hand, we have the trio of musicians, Emanu (Adrián Godínez on clarinet), Armando Monsiváis (guitar and beautiful original music), and Topé (Robert Moreno), on a set of bucket drums. They are also undocumented immigrants. A couple of runners-turned-into-ICE agents-turned-into-police officers, Lasca (Jennifer Stoneking) and Tiossido (Sixto Orellana), add to the farcical feel. They all do a fine job switching back and forth in multiple roles, seen and unseen behind the car doors.

In fact, the characters seem to know what is next, as in an endlessly replayed set of circumstances that senselessly repeats nightly. And, while each plays his or her part willingly, they are also very much aware of being played. Do not expect either the development of the action or the dialogue to make logical sense.

One point of observation is that some of these actors have strong speech accents. For me, it is a welcome relief to honor and respect those who have had to learn other languages to survive by emigrating elsewhere. Cardona’s directorial and casting choice honors those “with an accent,” elevating this type of speech pattern rather than ostracizing it or white-washing it. Actors with accents are perfectly intelligible. No need to make everyone sound Anglo.

There are innuendos of sexual and child abuse, some of which mix with humor. For me, it generated mixed feelings of repulsion and awareness. In parts, I could not tolerate the audience’s complicit laughter with the abusers, a mechanism I am aware of in terms of the absurdist representational tactics. It nevertheless unsettled me as I caught myself asking “what are we really laughing about here?” In some sense, this carnivalesque fiasco is somewhat reminiscent of the current political climate in U.S. national politics.

In the past, some critics have suggested that each character represents the passion of Christ, for me the most evident is that of the relationship between Jesus and Judas Iscariot. With Arrabal, the apocalypse is inevitable. A rarity of theatre, this play should be seen not only by general audiences but by drama students alike.

(Teresa Marrero is Professor at the University of North Texas.)