Alfred Eisenstaedt shuns conversations that border on the philosophical or mundane. He finds words almost cumbersome, They cannot convey what he wants: the telling expression on a face or the revealing detail of a situation.

In the span of seventy years, Alfred Eisenstaedt’s photographs have captured the glamour and innocence of Marilyn Monroe; the quintessence of Wmston Churchill’s strength and irreverence; and the joy and hope for the future at the close of World War II captured in a coupie’s celebratory kiss.

These expressions and details have defined everything we know and have experienced about a period of history or a person. They are unforgettable photographs.

Yet Eisenstaedt is abrupt in dismissing any meaning and message in his photographs. »I’m a photographer mostly for myself. I enjoy myself, and many pictures I did in my life were mostly taken for my own enjoyment. »

And if an editor does not like a particular photo, Eisenstaedt is again characteristically derisive. « Editors and photographers don’t agree all the time. I have a different taste. I come from a school of pictorialists.

« I was not a photojournalist when I started. I didn’t know what photojournalists were at the time, I’m more or less a pictorial photographer. »

The older son of Joseph and Regina (Schoen) Eisenstaedt, Alfred Eisenstaedt was born on December 6, 1898 in the West Prussian town of Dirschau, Germany (now Poland), The family moved to Berlin in 1906 where they lived comfortably from the success of Joseph Eisenstaedt’s department store.

When he was 13 years old, his uncle gave him an Eastman folding No.3 camera for his birthday in 1911, hoping the boy would take an interest in the new gadget, and possibly tum it into an engaging hobby. Eisenstaedt remembers quickly losing interest in the camera.

Graduating from the strict Hohenzollem Gymnasium in 1916, he was drafted into the German army and sent to Flanders where he served as a field artillery cannoneer. His military career ended during the second western offensive when a British shell struck his position-leaving both his legs badly injured by shrapnel. His companions were killed in the attack.

The aftermaths still haunt Eisenstaedt. On a trip to Verdun, he vividly recalls being overwhelmed by memories of the water-filled craters and the stench of the dead rising from fields strewn with body parts, To this day, he dislikes taking photographs of war and its attendant horrors.

After spending a year recovering from his wounds, Eisenstaedt entered university, where he indulged his passion for fine art, especially painting, by spending much of his free time in Berlin museums. He also took up photography again-this time, seriously.

Gripped by the « photo bug, » he spent most of his money on photographic equipment and on supplies for a primitive darkroom he set up in his parents’ bathroom.

In 1927, he sold his first photograph to Der Weltspiegel, an illustrated Berlin periodical. It was of a young woman playing tennis during the late afternoon, taken while on vacation with his parents in Czechoslovakia.

He was intrigued by the long shadows that the woman cast during her playing, but was dissatisfied with the other elements in the picture.

« In that photo, the tennis player was very small and the trees and benches in the background were very large », he recalls. So he asked a friend what he could do about it, and was told to enlarge the tennis player.

« I did not Know what « enlarge » meant. » Eisenslaedt admits. But once his Friend showed him the technique, a whole new world was waiting for him.

For that first picture, later titled « Autumn. The Shadows Grow Longer », he got 12 GM. ($3). Impressed by the photograph, the editor of Der Weltspiegel asked Eisenstaedt to bring him more work. Three weeks later, Eisenstaedt sold him another photograph.

Soon he was selling his pictures as a freelancer to periodicals and papers around the country and becoming one of the leaders of Ihe new art of photojournalism.

In place of the stiff and formalized photographs of the early part of the century. Eisenstaedt and other photographers emphasized spontancity and realism. They also began promoting the use of smaller and lighter cameras that allowed a photographer to move more freely around their subjects and scenes.

In the Berlin of the ’20s, in the metropolis of Brecht’s The Three Penny Opera, Marlene Dietrich’s Blue Angel, and Josephine Baker. Eisenstaedt’s career and growing recognition seemed assured.

Then, in the ’30s, he once again had to set his camera aside.

On October 29, 1929 the American stock market crashed, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jazz. Age ended with stockholders ruined, banks and businesses closing and unemployment rising to staggering levels. The Great Depression had begun.

Eisenstaedt’s family lost everything in the Crash. Having to help out, he went to work in a local « five and dime » selling sundries. But he couldn’t concentrate on buttons and belts. He was more interested in music, theater, and of course, photography.

« My boss considered me a very bad salesman. He said, « Mr. Eisenstaedt, you have to make up your mind within a week whether you will continue to sell buttons and belts or-what do you call the other thing you are doing? » And I said, « Photography ». He didn’t even know it-it didn’t exist.

« A week later, I told him I was starting photography. He looked at me as if I had dug my own grave ».

Five days after sealing his fate, he was on his way to Stockholm to photograph a Nobel Prize winner, Dr. Thomas Mann. Dr. Mann had received the award for Literature for his novels Buddenbrooks and The Magic Mountain.

« For the second assignment I got from the Associated Press. I traveled to Assisi to photograh the wedding of King Boris of Bulgaria to the youngest daughter of Ihe King of ltaly. Only, I was so fascinated by the pageantry going on that I forgot to photograph the bride and groom.

Then I came back to Berlin and they said, « Where’s the bride and groom? » And I said, « I haven’t seen them ». I saw Mussolini and all the kings strolling by and it didn’t even come to my mind to photograph the bride and groom.

« Associated Press in London said I had to be fired. But they couldn’t fire me-I was a freelancer. »

Following that embarrassing experience, Eisenstaedt was soon traveling around Europe on a variety of assignments for Associated Press. He recorded on film the Reparation Conference and Monitor Conferences; the Geneva League of Nations; he photographed the royal family in Sweden and flew with the Graff Zeppelin to Rio de Janeiro.

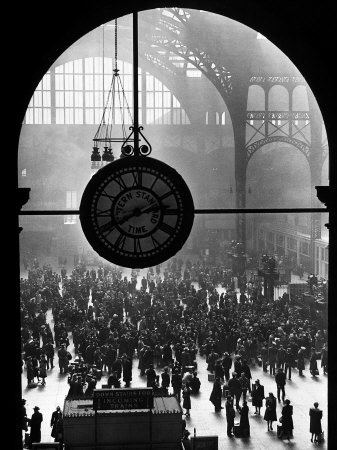

At the Grand Hotel in St. Moritz, he captured the acrobatic finesse of a black-tie-and-tailed waiter on skates, balancing a tray with bottles and glasses; and at the La Scala Opera House in Milan, he took the famous picture of the opera boxes with a beautiful woman in the foreground.

Many of these early photographs appeared in such European publications as Die Dame, Berliner Illustrierte, Graphic, the Illustrated London News, and Der Weltspiegel.

« In 1933, I was sent to Geneva where I photographed Goebbels, the famous picture of Goebbels looking at me. In 1934, I photographed the handshake between Mussolini and Hitler in Venice. And two months later, I photographed him, Hitler-the first time in uniform-attending the funeral of President Hindenburg in Tannenberg in East Prussia. I was standing about ten feet away from him ».

Asked about the terrible events beginning to sweep though Germany with the growing power of the Nazis and Hitler’s assumption of the chancellorship of Germany, Eisenstaedt says:

« At that time, we didn’t know. This was not America. We didn’t know much about anything. I was there when all these putsches were taking place. I was very much afraid. But I never had trouble. I had a permit to photograph, because I had been active in World War I. I got the Iron Cross. »

His distinguished service in the Kaiser’s army and his growing reputation as a photojournalist (in 1935, Associated Press published his pictures of Ethiopia’s preparations against Mussolini’s invasion which would occur a year later) could not protect him from the growing anti-Semitism and the Nazi campaign against the Jews.

In 1935, Eisenstaedt asked the Propaganda Ministry to remove his name from its list of photographers who could work in Germany and soon after, left for the United States.

« Everything was different. I met these people from Time magazine and the editor of the Berliner before he came to America. He gave Mr. Luce an idea to start a photo magazine. That photo magazine was called Magazine X. This is what became Life magazine. They told me if Life would ever start, I would be hired. And they did and I was.

« When they started Life magazine, it was old hat to me. I had done all this in Europe for years. »

Along with photographers Margaret Bourke-White, Thomas McAvoy and Peter Stackpole, Eisenstaedt developed Life magazine’s pictorial essay style and format. Like never before, photographs were to convey the emotional immediacy and essential nature of the story instead of the printed word.

Life magazine first came out on November 23,1936 with « Eisie » (as he became known among his new friends) leading the way.

One of his early assignments, which was to showcase the magazine’s new and innovative approach to photojournalism, was a picture essay on West Point. The picture of the stiff-backed plebe at the dinner table became the cover for the second issue of the magazine and seemed to express everything West Point symbolized. It was the first of many cover photos Eisenstaedt would produce.

Henry Luce, writing of his years working with Eisenstaedt at Life magazine, recalled: « Eisie showed that the camera could do more than take a striking picture here and there. It could do more than record « the instant moment ». Eisie showed that the camera could deal with an entire subject-whether the subject was a man, a maker of history or whether it was a social phenomena. That is what is meant by photojournalism ».

The photoessays also established his reputation as a photographer of enormous patience, persistence and, most of all, empathy.

« To have patience is the most important. You know, my type of photography; I’m different. I do not have any style. People can’t say, « This is an Eisenstaedt picture ». There isn’t an Eisenstaedt picture. I have no style. I do so many different things ».

After receiving his American citizenship, Eisenstaedt traveled to Japan to record the devastation of the war. In Hiroshima, he saw a mother and child among the ruins of the city.

« They were looking at some green vegetables they had raised from seeds planted in the ruins. When I asked the woman if I could take her picture, she bowed deeply and posed for me. Her expression was one of bewilderment, anguish and resignation… all I could do, after I had taken the picture, was bow very deeply before her », he recalls.

He later accompanied the late Emperor Hirohito on a series of tours around the country to see the destruction of the American bombings and the horrible power of the atomic bomb.

After a time, Eisenstaedt began turning his camera to portraiture, a continuation of his belief in the pictorial nature of his work. The same care he exhibited in his journalism is evident in the way his portraits capture something essential about their subjects.

Among the famous people he has photographed are Ernest Hemingway, Marlon Brando, Albert Einstein, George Bernard Shaw and Bertrand Russell.

Some of the famous women he has photographed include Marlene Dietrich, Sophia Loren, Marilyn Monroe and Ethel Barrymore.

« I click with people. I don’t pressure people, and I don’t tell them, « Do this ». I say « please ». And when somebody objects, I try to convince them. But if they insist they don’t want to be photographed-then I wouldn’t do it. »

Sometimes, his subjects can be quite difficult.

Chuckling, he remembers his attempt to photograph Churchill at Chartwell, his magnificent retreat, in 1951. Eisie arrived at twelve o’clock only to find his subject missing. With his customary patience, he waited. One hour passed. Two hours passed. He was beginning to get worried.

Just when he started to think that he should ask for Churchill’s whereabouts, the great man appeared. He was jovial, his cigar clamped firmly in his teeth, and very tipsy. Sitting down, he suddenly forgot Eisenstaedt’s reason for being there. Instead, Churchill had become engrossed in the mating rituals of a pair of guppies in his study’s fish tank and in the story about a certain captain and a large wave.

Eisenstaedt spent the whole time dancing around Churchill, who refused, even with gentle prodding, to look at the camera.

Later, when he traveled with Churchill on a campaign trip to Liverpool, the prime minister fell asleep while he was taking his picture. Noticing Eisenstaedt’s worried look, Randolph Churchill leaned over to his father and tapped him on the shoulder when the band played « God Save The King ». Churchill immediately bounced out of his chair and gave his famous victory salute. Eisenstaedt snapped the shot.

Probably his favorite subject, and the one who was easiest to work with, was Sophia Loren. He amusingly recalls that his cover photo of her in a skimpy negligee lost the magazine 800 subscribers and flooded the mailroom with 2,500 letters of complaint.

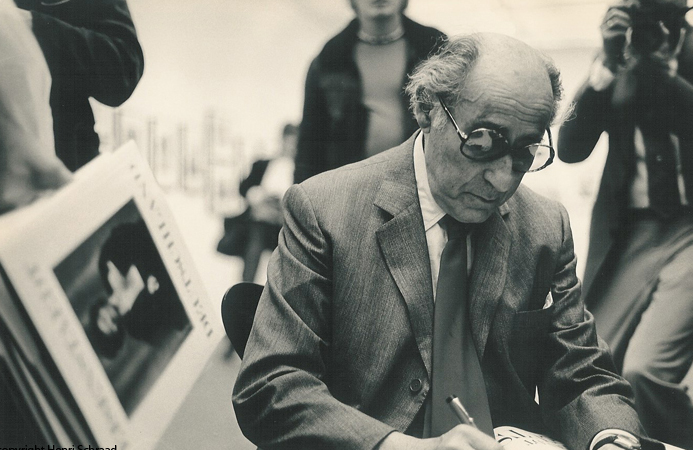

Since the 1940s, Eisenstaedt’s photographs have appeared in major exhibitions around the world.

In 1954, the Dryden Gallery of the George Eastman House displayed 300 of Eisenstaedt’s pictures for a celebration of his twenty-fifth anniversary as a professional photographer. E. Leitz Inc., the manufacturer of Leica cameras (which Eisenstaedt popularized), sponsored a traveling exhibition of his works; and in 1966-67, his solo exhibition « Witness To Our Tune » attracted record numbers in its tour of the United States. The photographs which appeared in the exhibition were later reproduced in Eisenstaedt’s first book, Witness To Our Time, published in 1966.

Several of his other books include The Eye of Eisenstaedt (1969), an amusing anecdotal autobiography; Martha’s Vineyard, a collection of pictures taken at the island off the coast of Massachusetts; and Wimbledon: A Celebration (1972), with an accompanying text by John McPhee.

In celebration of his 95th birthday the Circle Gallery in Manhattan recently held an exhibition. The show, « 95 at 95 » showcased 95 of his most famous and best photographs.

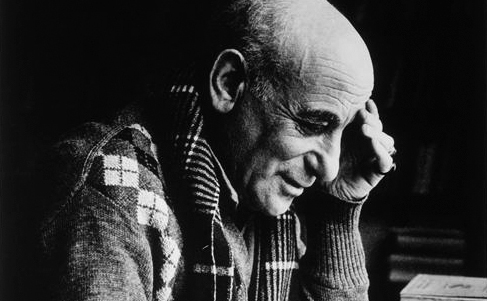

Possibly the most difficult person to photograph is Eisenstaedt himself. Famous for his ability to capture the essense of a moment or person, he himself is hard to catch. Even the greatest photographer of our time, Yousuf Karsh-whose photographs have defined our images of the famous and great-seems unable to capture him on film.

« Vis a Vis, the magazine, did a story on American legends and they wanted me. They assigned Karsh to photograph me. He came here and stayed almost three hours. He said the picture never came out!

« It’s unbelievable! This is Yousuf Karsh! He has Gordon Parks, Bernstein, but my picture didn’t turn out. »

A few days later, Karsh approached him during a dinner party. When Eisenstaedt asked what the problem was, Karsh looked at him and said, « The essence ».

« It’s very difficult. From now on, I say no to photographers who want to take my picture. They never come through ». But Annie Leibowitz, famous for her Vanity Fair shots, did his 95th birthday picture on the Brooklyn Bridge, and succeeded.

source : ronagam.com

Eisie had an incredible sense of humor and was gifted with incredible wit. I was so impressed by his candor and almost childlike curiosity. Rarely was I so touched by a man in his nineties that had this incredible connection to people. A few time, I followed him in his conferences and each time, it was an absolute delight to see this man almost 94, turning the audience on its feet with jokes and spirit. What lesson of life, it was. My deduction is that some of these geniuses keep their “inner child” alive all their life.

Thanks for these generous comments and sharing knowledge on a great man.

Le Leica d’Eisenstaedt eût su saisir Schumann in extremis alors même qu’il enjambait le pont de Düsseldorf d’où il se jeta dans le Rhin.

«Chapeaux bas, Messieurs, un génie!»